Bamboozled: Narration and Racial Power Struggles Through Camerawork

Examining the way Bamboozled narrates and details racial issues and power struggles through effective camerawork

Spike Lee’s 2000 film Bamboozled was seen by many (including the late Roger Ebert) as being too shocking to effectively convey the social message it had wrapped in its unusual satirical bent, steeped heavily in elements of Lumet’s Network. I’d like to examine some of the more subtle camera angles, movement, and composition to dig deeper into the way Bamboozled tells its story.

Disclaimer: I’m not trying to deconstruct most of the philosophical angle, since that has already been done. This is going to focus on visual and camera-specific aspects of the film.

Delacroix

“Satire, one: A. A literary work in which human vice or folly is ridiculed or attacked scornfully. B. The branch of literature that composes such work. Two: lrony, derision or caustic wit used to attack or expose folly, vice, or stupidity.” - Pierre Delacroix

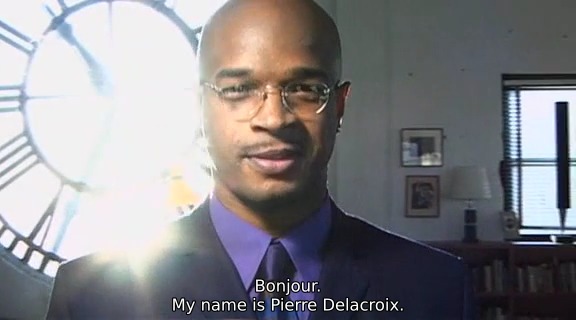

We open on Pierre Delacroix (literal French translation: “of the cross”), the nom-de-plume of Peerless Dothan (named after the Biblical city where Joseph was sold into slavery by his brethren) in his apartment.

The first thing to notice, besides the basic nature of the unconventional circular reveal of Delacroix, is that it’s counter-clockwise. As I have discussed in other visual breakdowns, right-to-left or counter-clockwise movement generally tends to indicate the villain – or at least someone who is at odds with the natural order of the universe.

The next three shots are expository, showing him getting up and ready for work. We start out at a distance …

… then move into some very tight shots of brushing his teeth.

But, like any film noir aficionado knows, a mirror is never just a mirror. This is going to resurface as a theme later on; for now it’s enough to know that Delacroix struggles with his identity. This we know without ever having heard him utter a single word.

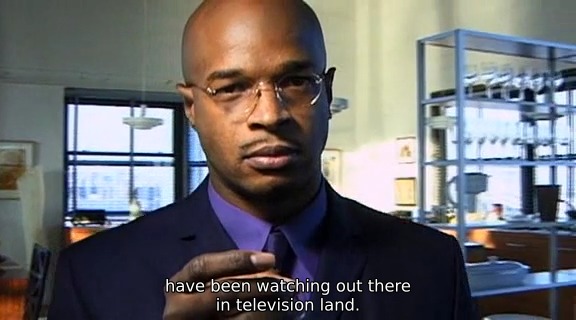

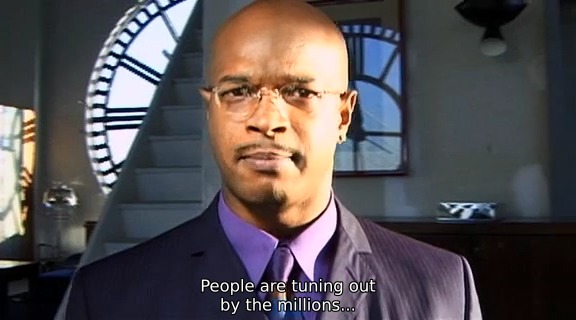

Suddenly, we enter one of the unique narrative aspects employed in Bamboozled. Delacroix is shown, employing frontality, to be directly addressing the audience of the film and introducing himself, ostensibly to us.

There’s a bit of ambiguity for a short while, as the jump cut to this shot (which is a single rotating dolly rig shot) does not prepare us at all for this narrative device.

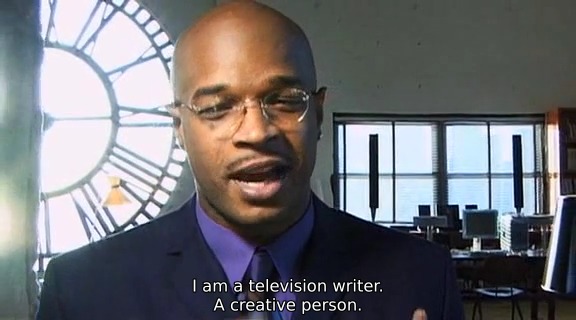

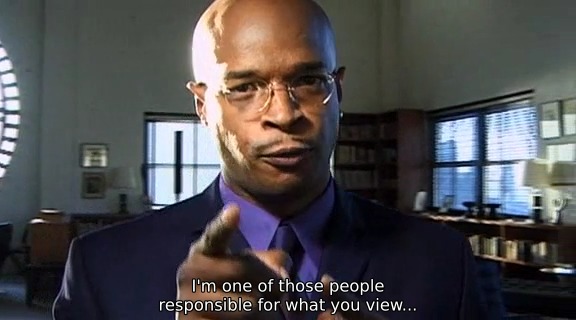

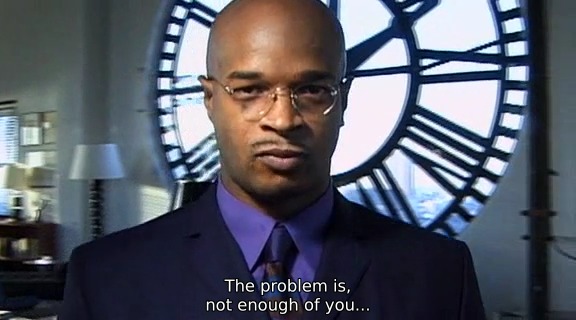

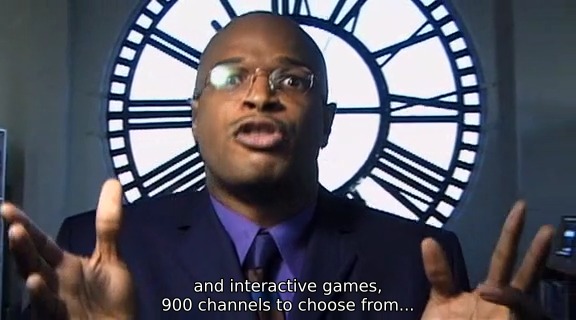

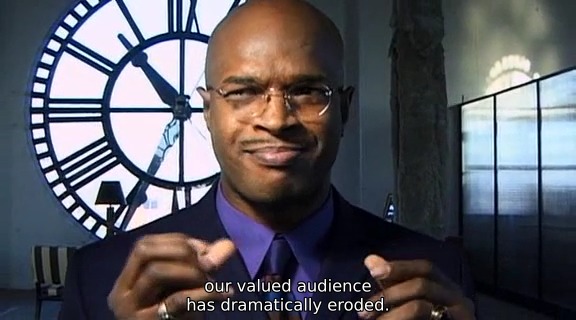

Now we’ve rotated completely around. Lee has shown us the entire space – and there’s no one else here. This entire monologue, with Delacroix literally in the middle of it – both the frame and the scene – is entirely for our expositional benefit.

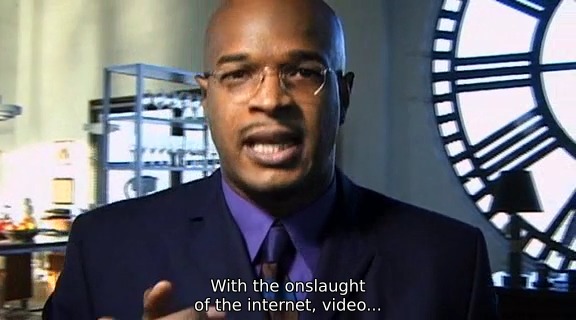

Let’s just say that the potential religious iconography isn’t necessarily that out-of-place. There’s a martyr arc being presented, and the “halo” provided by the clock subconsciously conveys that information, even as Delacroix rambles on about his job as a television executive.

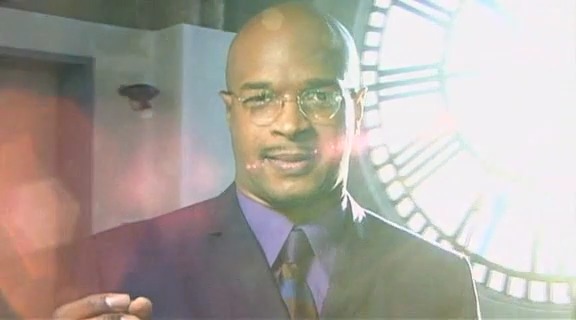

We end right where we began, as Delacroix disappears back into the flare (or as Sloan would later refer to it, “into the light”) as our expository trip around his apartment comes to a close.

It is clean, pristine – perfect.

Womack and Manray

To introduce Womack and Manray, we jump to a very canted view of urban decay, adorned with a nod to “Da Bomb”, a fictional blaxploitation beverage, to be featured later in the film.

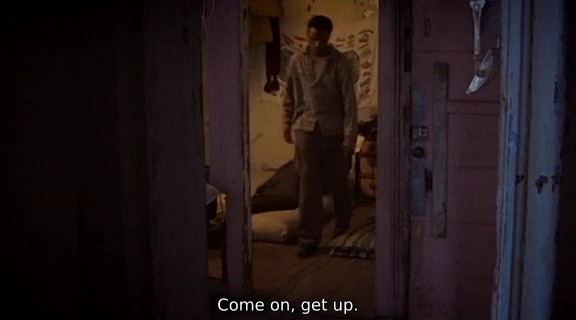

We cut to Womack, trying to wake up Manray. Even though the room is large, the camera is set at a low angle. We’re not setting up a reverse shot from Manray, even though that would be the obvious way to start a conversational scene – we’re pushing him up against the ceiling. Beyond the peeling paint and general signs of squatting and urban decay, the notion that these characters are trapped in a figurative corner is subconsciously conveyed by the composition:

Manray can’t even be shown in his entirety in this next shot – the wall is being used to push him further out of frame than we would ideally want him to be.

Even when the shot theoretically opens up, the artificial frame of the door delineates our “heroes”, colored by warmer light, from the colder color of the outside world:

This continues as they move outside:

… and with a scale shot. (Please forgive the lens distortion – I’m pretty sure it was a technical limitation.)

I’m going to skip past the introduction of Womack and Manray to Delacroix – not because it isn’t important, but because I’d like to analyze the following scene.

Dunwitty

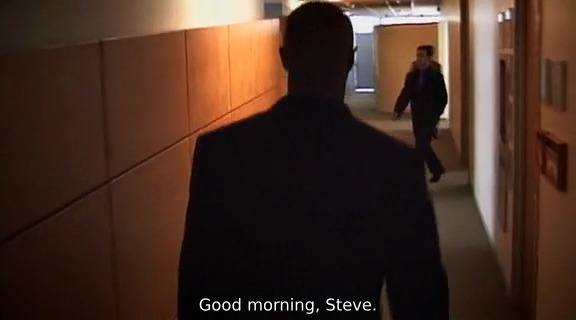

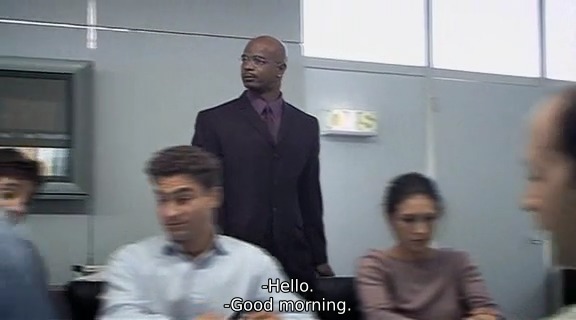

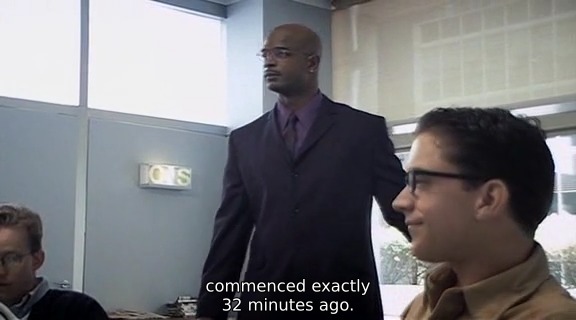

Delacroix is moving through the hallway, on his way to a morning meeting. He is attempting to be a part of a culture and society of which he is not. We’re back to dead-center framing as we follow him forward …

… and reverse the angle to lead him:

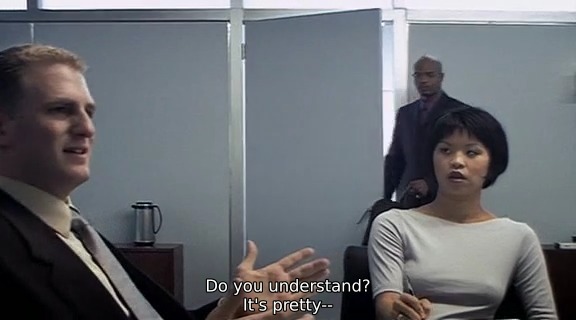

As soon as he enters the meeting, we can see that he is visually separated from everyone else. He is smaller and less significant than the sea of non-black faces …

… which he floats by. Even though he’s taller than them, the perspective causes his head to appear about half the size of the people seated on the far side of the table, and about a quarter the size of the ones seated on the near side.

We return to the original framing of Dunwitty, controlling the meeting. His eyeline is perceptually above that of the only co-worker we can see in the shot.

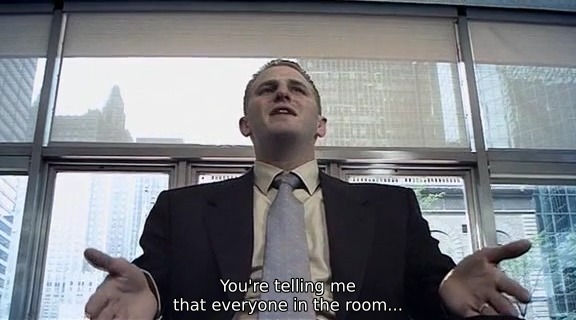

And now it gets interesting. As Delacroix is being talked down to by Dunwitty, we’re treated to a very skewed externalization of the standard shot / reverse shot. We are literally looking down on Delacroix …

… a quick jump into his head to try to rationalize what is happening …

… and the reverse. Note that this is very similar to the extremely low angle shot used in Network when Howard Beale meets the head of the network. Dunwitty is looking down on Delacroix, even though in the physical space being represented …

… the two men are actually at the same eye level. Even in the wide shot, Delacroix is as far away from the “seat of power” (where Dunwitty is sitting) as he can possibly be, boxed in by a sea of white faces. He is marginalized, both visually and in the context of the film’s story.

When we show a reverse shot, even though the camera is higher, we only see the back of Delacroix’s head. He is depersonalized, and his eyeline is shown as being below Dunwitty’s, even though Dunwitty takes up less space in the frame. The two men are very visually shown to be at odds with each other.

The confrontation and dynamic of race is only implied in that scene, as the only racial reference Dunwitty makes is to compare Delacroix to Dennis Rodman (a black basketball player). In a subsequent scene, Dunwitty not only questions Delacroix’s “blackness”, refers to “CP time” (colored people’s time), but then proceeds to lay claim to being able to use “the N-word” because he married a black woman. The scene I’ve just described is only a prelude to this.

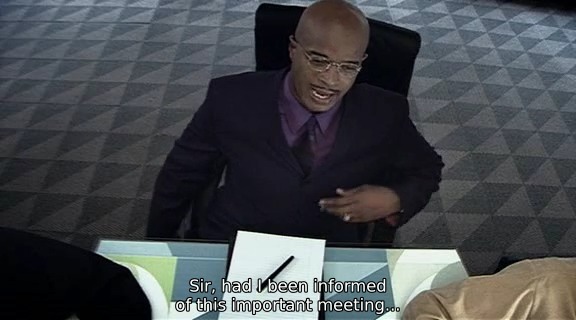

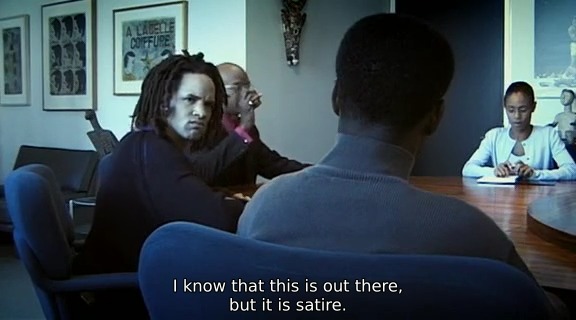

Next, I’d like to review the “pitch” scene, where Delacroix pitches “Mantan: The New Millenium Minstrel Show” to Dunwitty.

The Pitch

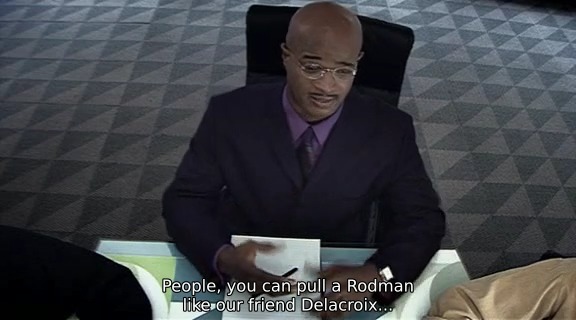

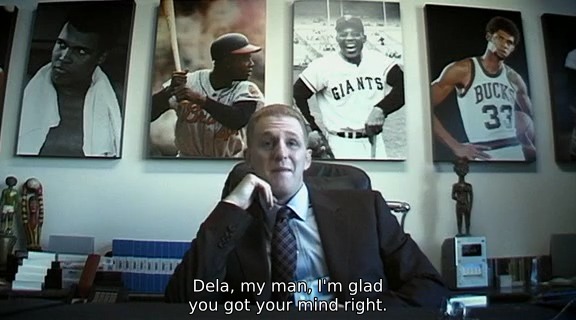

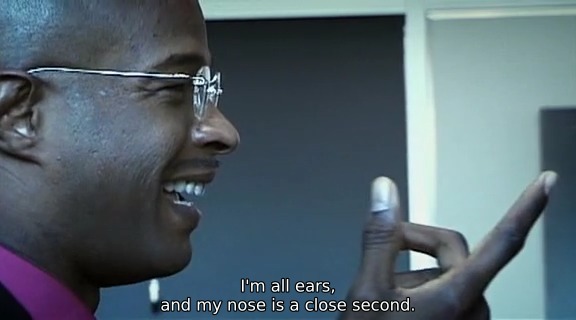

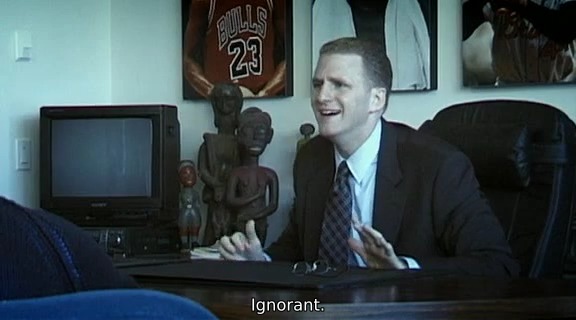

We start with Dunwitty in center frame. His head is exactly in the middle of the frame, and he is flanked by a row of black athletes and the glow of warm-colored lighting.

The reverse shot across the table is Delacroix from the same physical position on the table – which gives us an up-angle shot on him. Unlike Dunwitty, however, there is a clear physical frame surrounding him, reminiscent of the frame that we saw around Womack’s head in his introductory scene:

We move to a variant of the shot / reverse shot, with both men occupying the same eye level and mirror-like framing.

Lee jump cuts backwards, to show Delacroix, still boxed in …

… and pantomime eviscerating himself:

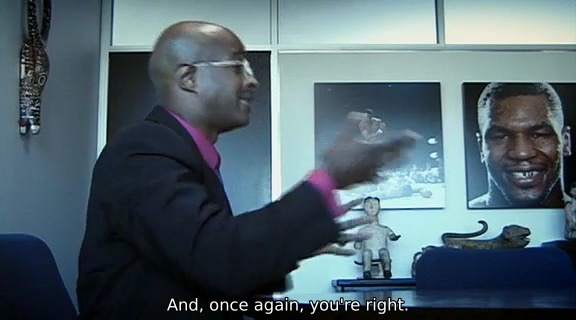

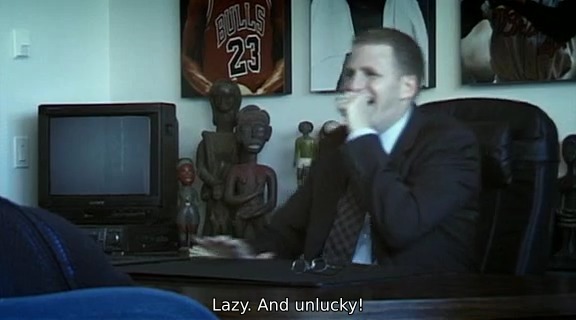

The reverse shot of Dunwitty also gains the same wider angle. Lee is very gradually exposing the space around these characters. We started with a medium shot to reveal the wall of sports figures and Delacroix being visually boxed in, even though he is in the middle of the room. Widening the shot as we move to a tight side view allows us to leave a few details of the room to be revealed, and allows a dialogue heavy scene to keep some new visual for a little longer.

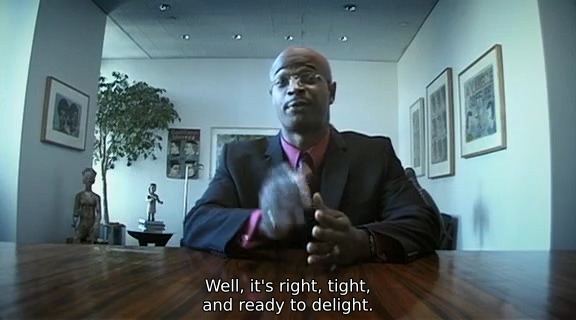

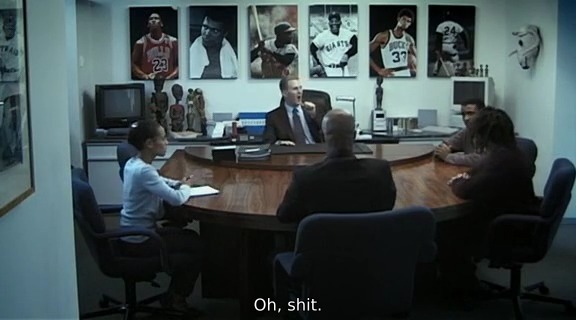

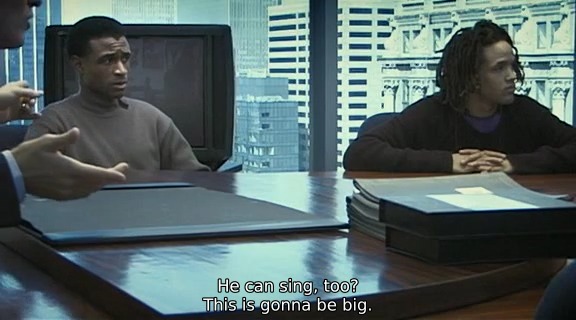

Skip forward a little bit, as Sloan, Womack, and Manray enter and sit down at the table. Dunwitty is almost dead center frame, surrounded by a sea of black faces – whether they be the sports icons he has behind him (both physically and metaphorically) or the semi-circle of supplicating underlings. Even though he is outnumbered in this shot, we’re never given the idea that he is left powerless ; he is controlling the shot and the scene.

Look at Sloan’s face when Delacroix starts using racially charged terms to sell the characters:

Now look at Manray’s face:

Back to Sloan:

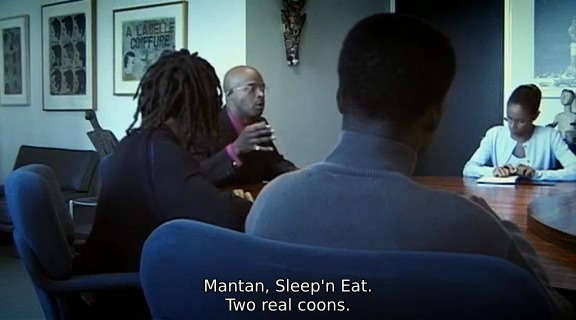

These are looks of shame and horror at the dehumanization they’re undergoing. They’re being trotted out – by one of their own (see the previous reference to “Dothan”, it makes perfect sense here) – to be sold to the network on a modern-day auction block. Notice that Delacroix is always near the center of the frame ; he is the driving force behind it, and is visually represented to be just that.

Contrast that with Dunwitty’s expression of glee at the descriptions of “Mantan and Sleep and Eat” as a series of racial stereotypes …

… and Sloan looking unbelievably at one of her own, selling them out.

Dunwitty is overjoyed.

We can now clearly see Womack’s expression, along with Manray’s – it is the same look of shame.

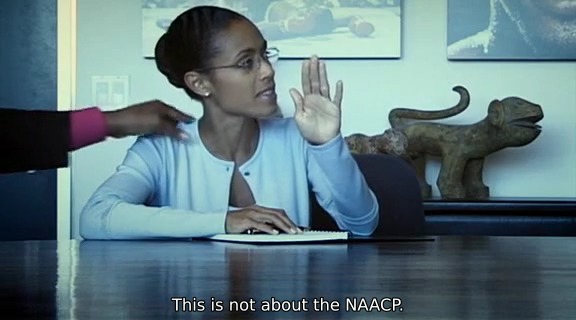

Sloan tries to protest …

… but Delacroix stops her by putting a hand on her shoulder.

It is worth noting that in this scene, other than the claustrophobic wide shot of all of the characters, Dunwitty is always shown separately from the other characters. The personification of the white power structure in the storyline doesn’t share diegetic space with the black characters. No matter how much they try to belong, we’re told visually that they never will.

A quick one-off shot of the same three despondent characters, claustrophobic in an open frame, looking at the pictures detailing their eventual degradation:

Dehumanization

“We gonna need a little more money for this.” - Womack

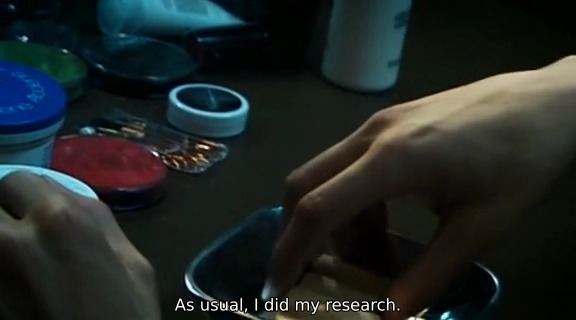

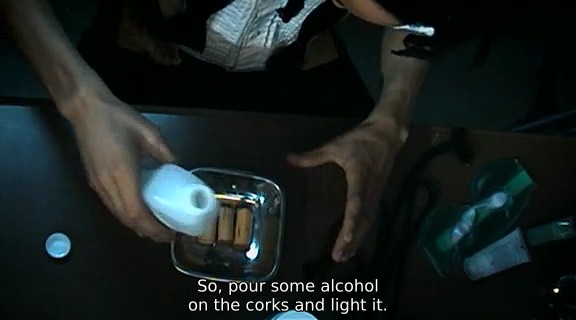

For the final scene being deconstructed in this article, I’d like to focus on one of the more painful and dehumanizing scenes in the film. It is the initial application of the blackface makeup, narrated by Sloan. As with many of my favorite scenes, it starts with a closeup shot, which is then cut back to reveal more of the scene. It’s better not to show your whole hand to the viewer, unless you stand to gain from it.

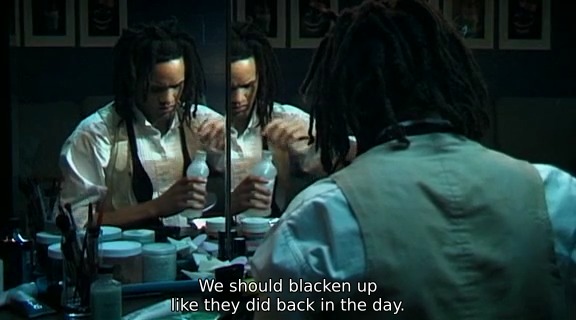

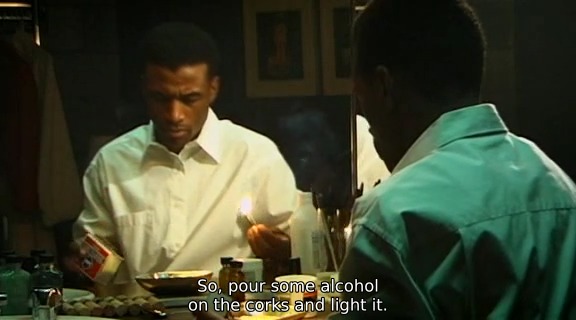

Manray is now pouring alcohol on the corks in front of a mirror. As I had mentioned earlier, this specifically indicates an identity struggle externally. Manray needs the money to survive, but what he has to do to earn that money is give up his pride by “blackening up” with burnt cork.

We’re treated to the same with Womack.

Manray is shown, marginalized in the far edge of the frame. Who he is as a person – it’s shown to be no longer important in the context of the story narrative. He has to stifle who he is so that he can dance for what is ostensibly the American Public.

He covers his eyes, hiding who he is.

And now, one of the single saddest shots of the entire film:

Womack is being robbed of his identity and individuality, and we can palpably sense this by seeing the hesitation with which he applies the first application of the blackface makeup.

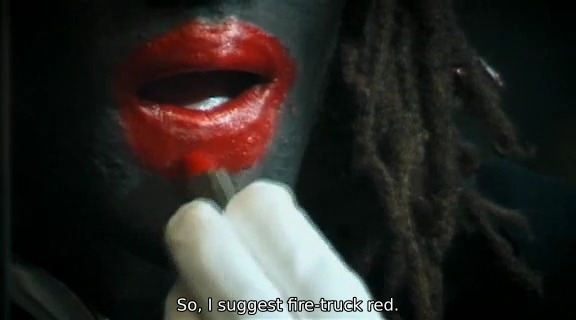

There is a very intentional, yet slight, cant going on here. The camera is tilted to the left by a few degrees, leaving an unsettling feeling about what we’re seeing. Coupled with the inherently dehumanizing visuals and the musical content, this creates all of the elements necessary for a moving scene.

Back to Manray, we watch his face become progressively more occluded by the blackface …

… as he stares at the fractured image in the mirror:

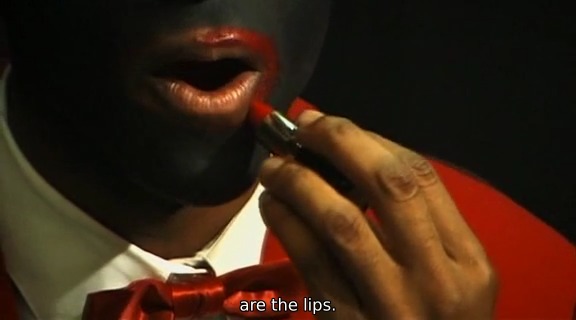

We continue to cross-cut between extreme closeups of the application process and the two men as they apply the “fire engine red” lipstick, as part of the exaggeration and final steps of the process of dehumanization they must endure:

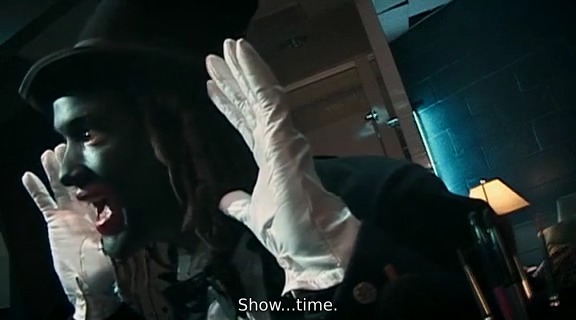

The process is complete, and the people who were Manray and Womack are now the marionettes who are “Mantan and Sleep and Eat”.

Satire

It’s satire – no one in their right mind would ever mount an actual minstrel show on television – but Lee has made his point; it’s not right to dehumanize people for the sake of entertainment (or for any other reason). As if to buck Poe’s Law, Lee actually included the textbook definition of satire in the opening voiceover before Delacroix introduces himself.

The art in Bamboozled comes much from Lee’s use of some of these subtle framings and compositions to tell a story without chewing through some of the film’s precious narrative exposition capital. There’s only so much expository narration that a viewer will tolerate before losing interest, and in a dialogue and content heavy film like this one, subconscious associations and framings go a long way toward making your point.

For more information on Bamboozled, please see:

- The Violence of Stereotypes: Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (cite)

- Not Coming’s Review “The Controversy of Race in Spike Lee’s Bamboozled” (cite)

- A Black-Centered Analysis of Bamboozled (cite)

- The Conversations: Bamboozled (cite)

- How Spike Lee’s ‘Bamboozled’ challenges Hollywood’s portrayal of black people on screen (cite)

(All images are presented under fair use guidelines – all frame grabs are property of New Line Cinema, 40 Acres & A Mule Filmworks, or any other entities who hold copyright on this film. They are presented for exclusively educational purposes.)