The Virgin Suicides: The Loss of Innocence and the Illusion of Normality

Examining The Virgin Suicides for visual clues

Sophia Coppola’s freshman feature film, The Virgin Suicides, initially struck me as a very disquieting film. Using the guise of average suburban life and teenage maturation rituals, Coppola delivers an interesting viewpoint on innocence and normalcy.

The rot underneath the facade of suburbia

“Everyone dates the decline of our neighborhood to the suicides of the Lisbon girls.

The film opens with what appears to be a montage of middle American suburban life. The coloring is warm, and the figures are just far enough away that you don’t really know anything about them.

From the girl sucking on a lollipop …

… to the man watering his lawn …

… to the women walking their dogs …

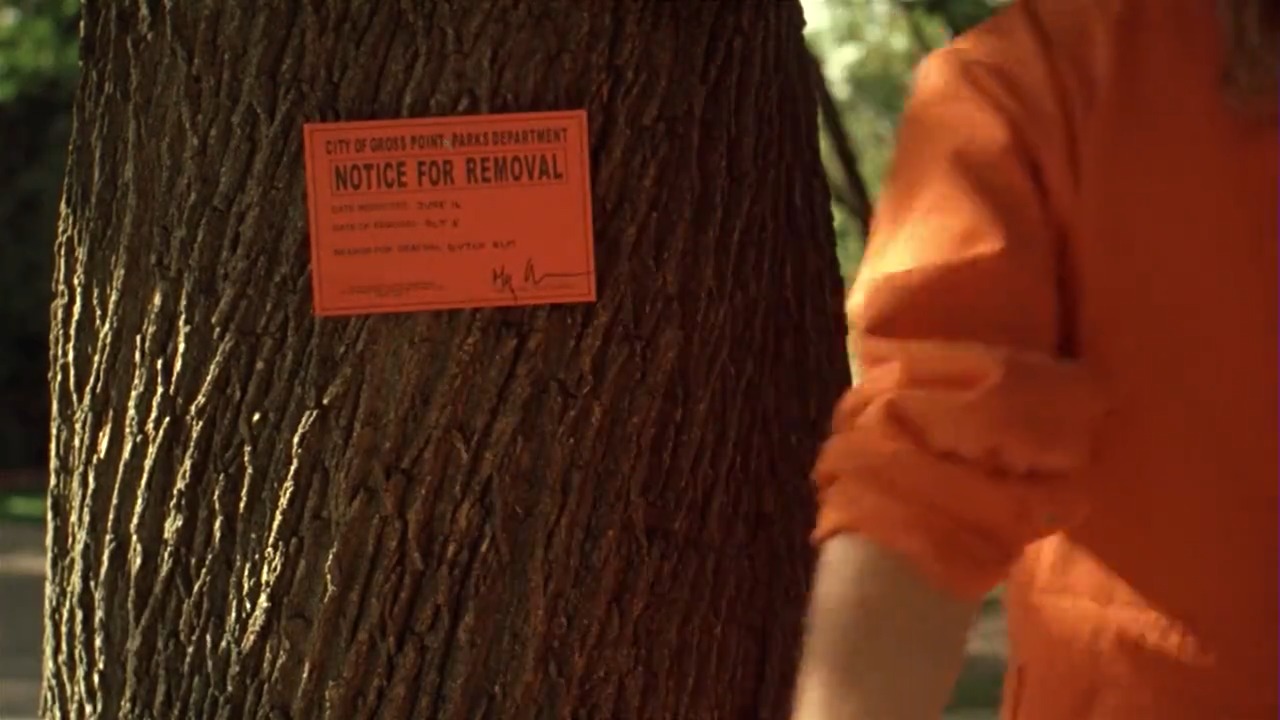

… to the workers putting a notice on a tree.

We don’t get any close shots until this one, which figures into one of the predominant themes of the film – even though we don’t know it yet. The tree has to be removed because it is infected ; there’s a worry that if they don’t get rid of it, all the trees will die.

Back to idyllic suburbia, with a very long shot of a father cooking on a grill and his son shooting hoops in the driveway. Even though they are the center of the action in this shot, at least two thirds of the frame above them is occupied by trees. The characters are kept anonymous and distant.

Back to the tree motif, we see a flare of sunlight glancing through the thick leaves…

… and then a quick color palette change, and we cut to a windowsill covered in the trappings of female adornment and beautification, with the sound of sirens in the background.

We cut to a God’s eye view of Cecilia, apparently dead in the bathtub.

Back to the warm glow of the suburban enclave, we see the neighborhood children looking out of frame at a sadness and horror that we cannot see. We assume that they’re looking at Cecilia …

… but they aren’t. She’s still being brought out of the bathroom:

As they carry her, we see that she drops a bloody card of the Virgin Mary. This religious thread is revisited in a few moments –

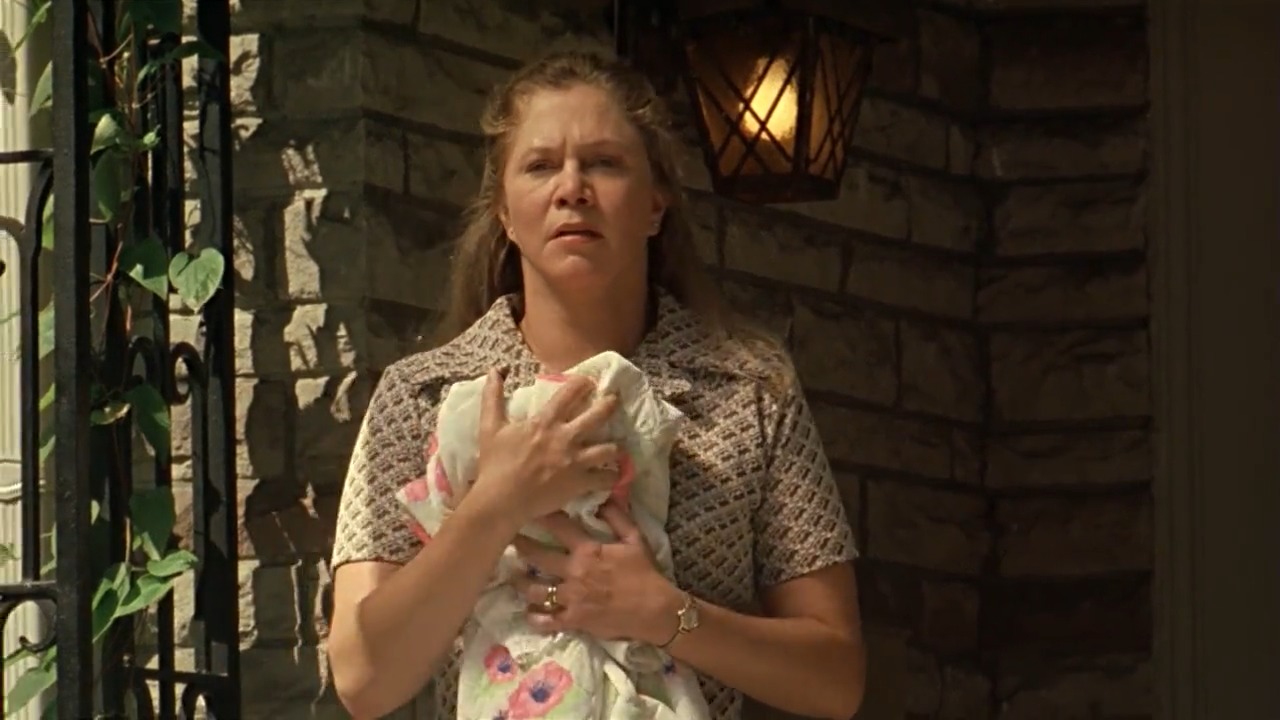

Mrs Lisbon emerges, carrying an article of clothing as the paramedics drive away. At first, we see that she’s very marginalized ; diminutive in the left third of the frame, while the ambulance takes up the other two thirds.

Her self-pity and worry is only brought first and foremost after the ambulance leaves. It’s all too little, too late.

The voiceover, “Cecilia was the first to go”, provides both misleading and foreshadowing information. Cecilia is not dead – at least, not yet. Coppola has given us all of the themes of the film in her first montage.

The notion of an idyllic suburban life, replete with gossiping and voyeuristic neighbors, overzealous religious figures, teenage drama, and a host of familiar but harmless characters; these are simply the window-dressing for the rot and dysfunction which lies beneath. The surname “Lisbon” means “safe harbor” – and this is subverted by the inability of the parents to keep their children safe.

The drastic change of color temperature between suburbia and the suicide attempt offer a contrast between the veneer of banal rose-colored existence and the dark truths that lie beneath.

Point of view

“Normal is the average of deviance.” - Rita Mae Brown

There are a number of interesting narrative schemes which are used to give expository information throughout the film, apart from the omnipresent voice of the narrator.

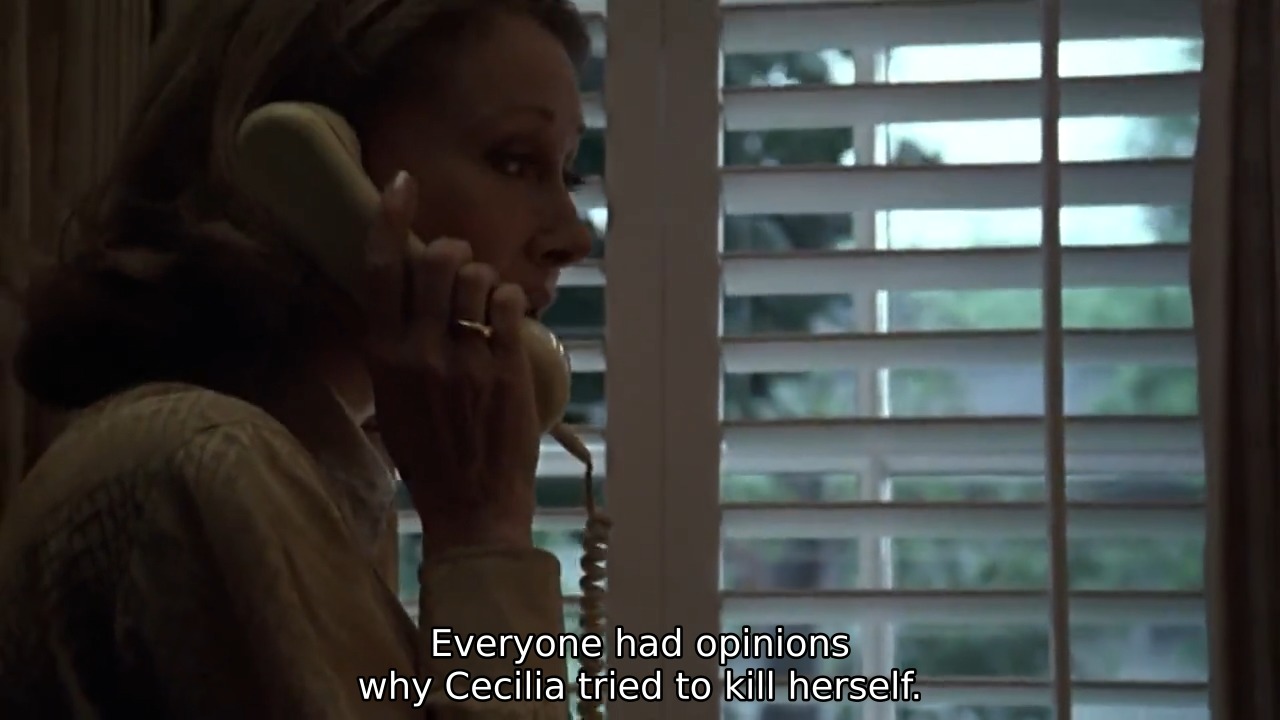

One is a series of gossiping neighbors. There are two such techniques, presented back to back, in the aftermath of Cecilia’s suicide attempt.

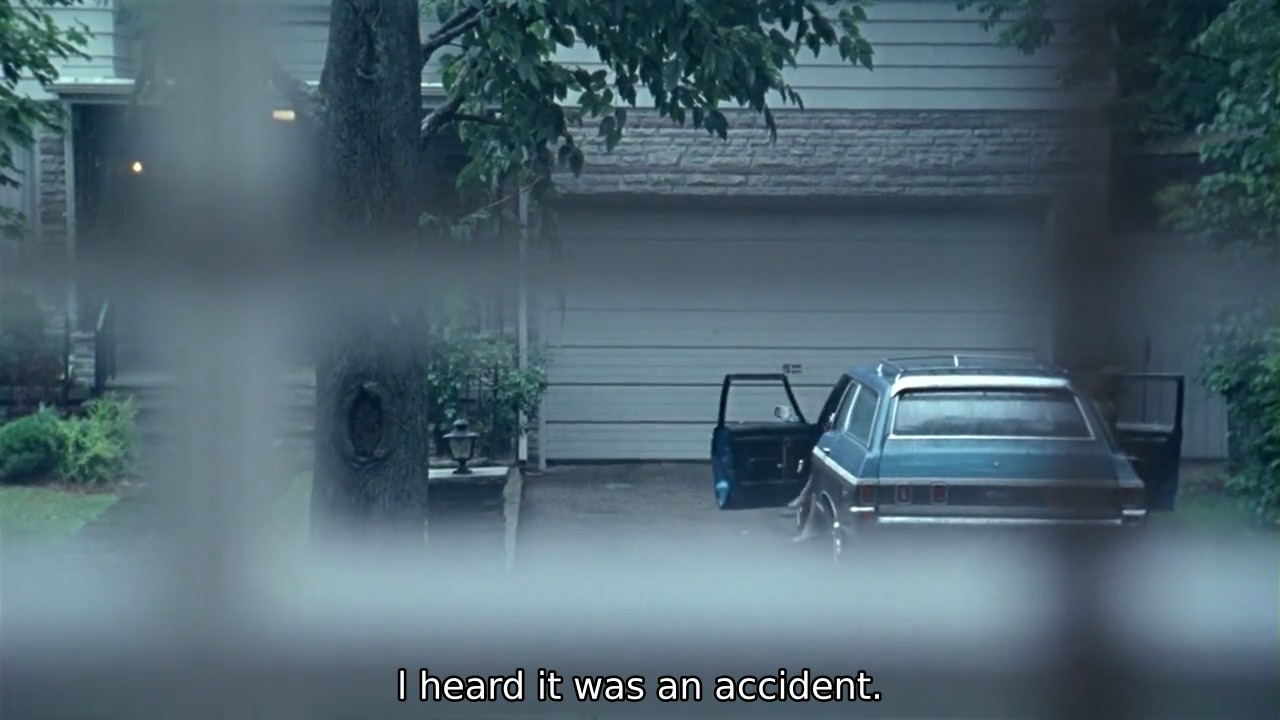

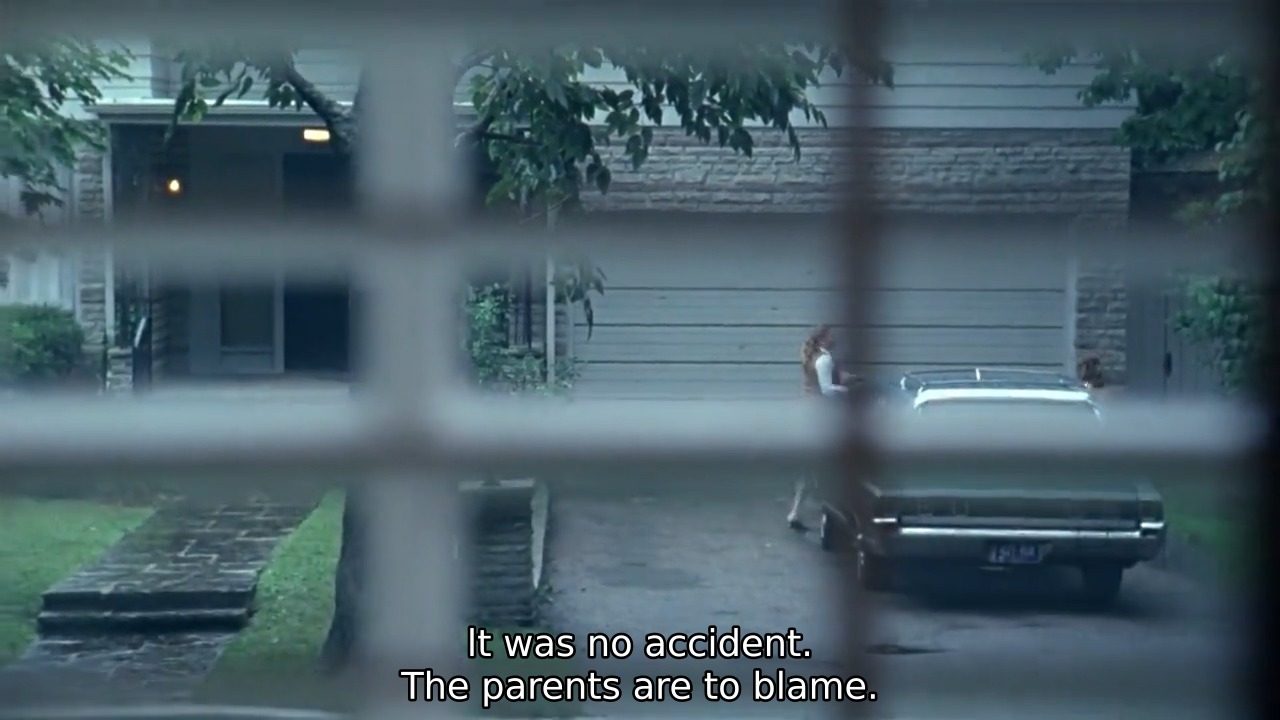

One is a drawback reveal shot from across the street.

It starts with on obvious window-dressing occlusion in a very voyeuristic shot of the Lisbon driveway, with the sound of a neighbor gossiping …

… and pulls back to reveal that the neighbor is on the phone:

This subverts the expectation that the disembodied voice, like our ever-present narrator, is speaking to us. The color temperature is cooler here ; we are supposed to infer that this is the hidden truth, whispered between co-conspirators, rather than an outwardly suburban false construction.

The next cut is an awkwardly framed shot of two women, sitting in front of a very prominent window. They occupy a very small part of the frame, even though the house is, much like the exteriors we’ve seen, using a very warm color light.

These women are dwarfed by the outward appearance of their living quarters, and the majority of the frame is occupied by literal window dressing. We could assume that this is an objective narration to the camera, except that their eyeline skews to the left of the camera. They’re not speaking to us, but rather to the visitor (or visitors) sitting across from them. This gossip is less about hushed tones and more about the general outward fabric of the neighborhood.

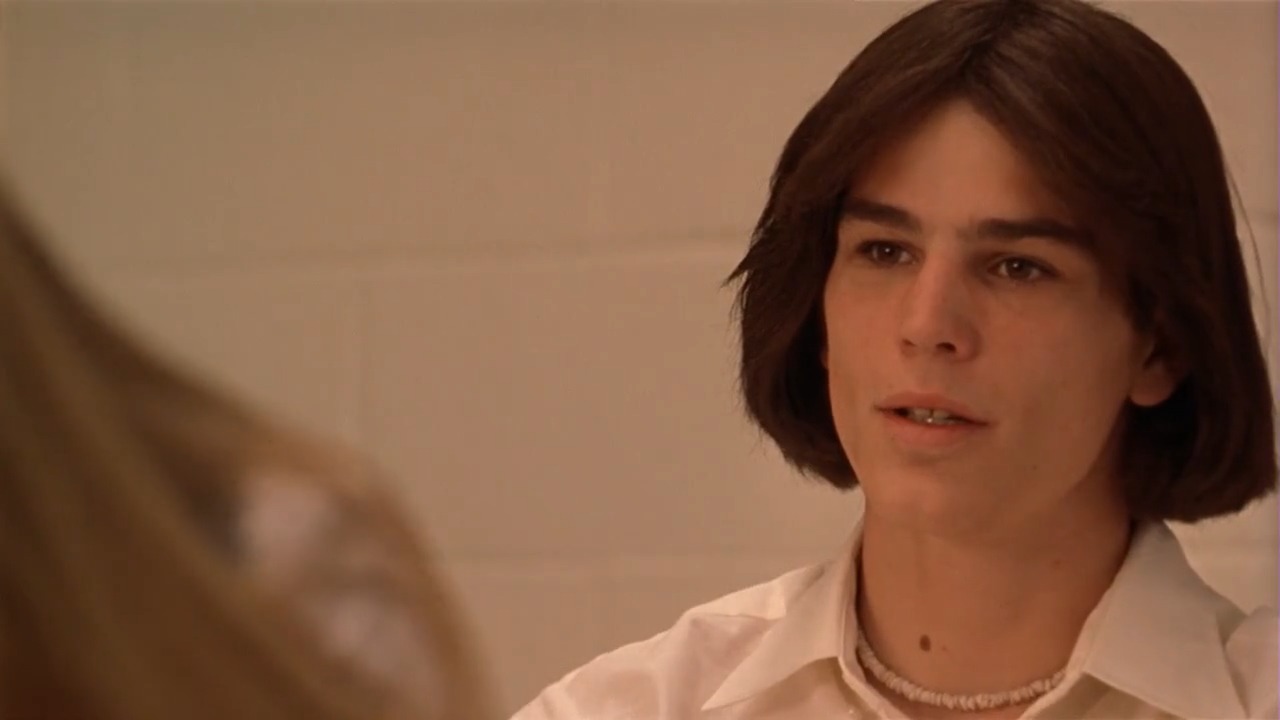

For the last narrative style I’d like to go over, we have to skip ahead in the film quite a bit, to the introduction of Trip Fontaine.

We transition from a shot of Trip, sitting behind Lux in class …

… to a shot of Trip, much older, reminiscing at a table with a cup of coffee and an ashtray.

He professes that what he and Lux had was “love”, but we get the very distinct impression that he’s talking about lust and sex, not love. He’s looking directly at the camera, but it’s unclear as to whether he’s talking to us or someone who is sitting in the seat across from him.

Later on, after he abandons Lux on the football field, we revisit him in this interview settings:

The color is cooler, and Fontaine seems far more subdued and saddened than when we initially saw him.

The last reveal related to the character of Trip comes in the form of a scrubs-clad nurse, informing him that it’s time for a group meeting, implying that he is in a mental care facility, as he finally breaks from the full frontality with which we have been viewing his adult self to acknowledge her.

Trees

“Girls, girls, it’s a little late – this tree is dead.”

The elm trees, which are featured throughout the film’s visuals, have a metaphoric value. They are nature, beauty, goodness – all of the things which are perverted and hidden, torn down and maligned for the sake of the veneer of suburban perfection.

After her suicide, we learn from her diary that Cecilia wrote extensively about the trees dying. The boys, whose viewpoint the film is seen through, dismiss her apparent obsession with the dying trees as we, the viewers, are given vital expository information.

Even as she commits suicide, Coppola pulls back so that the lowest branch of the elm is in frame as Mr Lisbon holds the body of his daughter and his wife tries to shield her remaining children from the reality of death.

It’s telling, in a way, that the warmer color temperature of the tungsten lights inside should be contrasted with the cool blue of the apparent exterior moonlight ; it contasts the warm idyllic innocence supposedly offered by the protective religious household of the Lisbons with the cold reality of the cruel and heartless truth, hidden below the surface of suburbia.

Later on, workmen arrive to cut down their Elm tree.

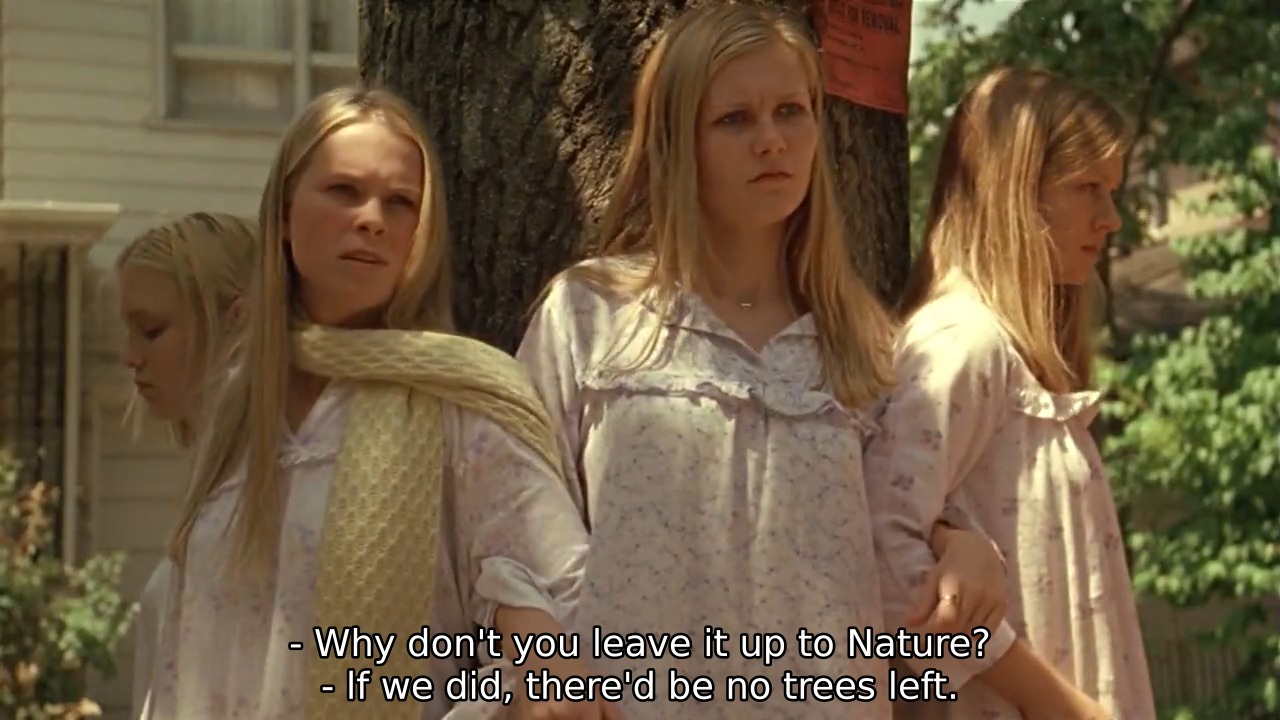

The girls form a protective ring around the tree, locking arms.

The foreman informs them that the tree is dead …

… but they ask why it can’t be left up to nature?

The foreman says there would be no trees left. Lux then says …

The foreshadowing here is pretty heavy handed, but the point is made. Messing with the balance of nature, even in attempts to save it, won’t prevent its inevitable destruction. Mr Lisbon’s reaction to his daughter jumping to her death on the fence in the front yard (which has been noted to be a reference to her being on the border of womanhood) is to have that fence removed – as if removing the symptom would alleviate the sickness.

Cecilia’s poems made reference to trees producing the oxygen which we need to survive. It seems as though this expands upon the existent tree metaphor, as the loss of the Elm trees closely parallels the loss of the Lisbon girls.

Lux’s relationships and composition

A great deal is shown by the composition of the shots detailing Lux’s different relationships – and the differing parts of those relationships.

For example, her courtship with Trip is typified by close shots, warm tones, and an intimate atmosphere. In the shot where he first notices her, we are rack focused from blur to focus, externalizing the internal process of Lux coming into focus for Trip:

She is the only thing in the frame, perfectly representing his view and singular obsession with her.

As the courtship progresses, we see elements of colder colors introduced as it becomes less innocent …

… as Trip tries (and fails) to hold her hand in the auditorium. After a failed attempt to ask her out, he is shown to be enclosed in his car, trapped and confined …

… until Lux is introduced as an element. We can see both warm and cool light colors as they finally kiss. The mix is about half and half now.

As Lux loses her innocence on the football field, everything is lit in blue moonlight, with the exception of the flash of warm colored tungsten headlights:

The next day, her innocence gone, Lux is bathed in almost unnaturally blue light.

This is further accentuated by the exceptionally wide framing, showing how alone and vulnerable she is.

Asleep, she was centered and held by the confines of the frame, but as we move to the wide shot we can see that the illusion of happiness and comfort was just an illusion – she is completely alone.

Her two other encounters with boys on the roof are shown voyeuristically through telescope glass, but dark and bathed in blue light. There is no innocence left to be had.

As this has grown rather lengthy, I’m going to save the rest for another time.

(All images are presented under fair use guidelines – all frame grabs are property of American Zoetrope, Eternity Pictures, Muse Productions, or any other entities who hold copyright on this film. They are presented for exclusively educational purposes.)