The Life and Death of Peter Sellers: Interweaving Epistemological Layers and Being Other People

Exploring character through layered epistemology in The Life and Death of Peter Sellers

Peter Sellers was an enigmatic enigma – at least, if we are to believe the 2004 biopic The Life and Death of Peter Sellers. This film combines a fascinating biographical picture of Peter Sellers the man with the relatively unused technique of sliding effortlessly between not only epistemological layers, but also expository styles and even points of view. Peter Sellers effectively retcons his life.

Breaking out for the first time: Choosing a narrative voice

One of the central themes in The Life and Death of Peter Sellers is that Sellers didn’t really have a personality of his own – that he essentially lived through his characters. It is used to explain away some of the more awful aspects of his personality, much the way Harry Block is “a guy who can’t function well in life, but can only function in art” in Deconstructing Harry. The more novel aspect of this film is that it shows this visually, by allowing us to seamlessly shift between epistemic layers like The Adventures of Baron Munchausen – but to an even greater degree. Munchausen had actors playing actors serving as characters, whereas Sellers has actors interchangeably playing actors and acting, and Geoffrey Rush playing Peter Sellers playing everyone else.

For the first of the scenes to be deconstructed, let’s look at Peter receiving an acting award, while his parents watch on the television.

We open with the entire proceedings being framed by a period television framing a black and white image of the ceremony.

We cut to a medium shot of Peg, Peter’s mother, anxiously anticipating the outcome of the award presentation. We’re given almost no context for this ; as far as our diegetic world is concerned, we only know about Peg and the ceremony – if another character were present, we definitely don’t know about them yet. This is one of my favorite scene opening techniques: saving a bit of information for a few moments longer by withholding wider shots until all of the important plot elements have been revealed.

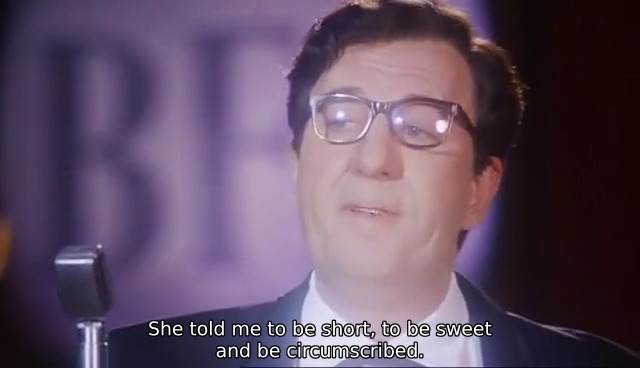

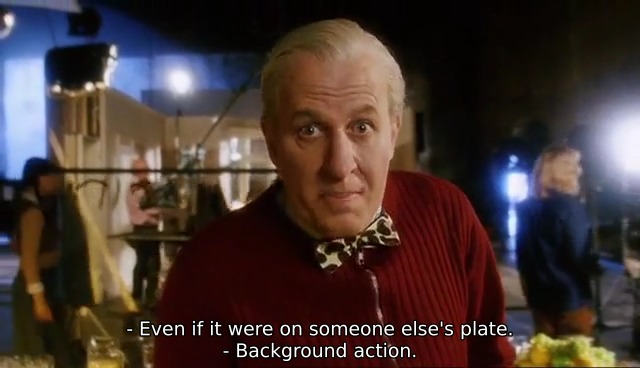

Back to the ceremony. This is a bit of an odd shot, as it’s in color, so we can take away the implication that we’re in the awards ceremony – but it’s a little washed out in a way that evokes the feeling of watching this on Peg’s black and white television. The only saturated color element is the curtain behind the actors ; as if to imply that the pageantry matters more than the figures appearing in front of it.

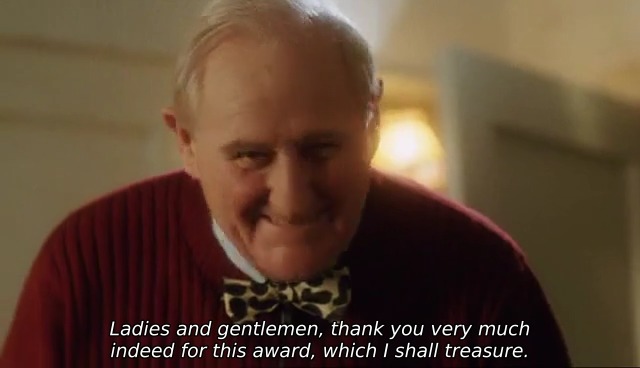

Finally, we get a moderately wide shot of Peter’s parents, as his father enters through the sliding doorway. It’s important to note that we only saw Peg watching this scene as her husband dotes on her. It’s part of an overarching theme of a dominating state mother accompanied by an emasculated and minimalized father. He’s happy for his son, but his reactions are far more subdued than Peg’s.

Peter accepts the award, which we see through the lens of the television. His parents (most notably Peg) are separated from his public life, represented visually by the television image – the literal frame around the image, thick glass, and fuzzy image form a close-to-perfect metaphor:

We get very objective response shots from the parents, one at a time, as reverse shots to the television. The frontality with which we are presented presents an interesting shot, as we are looking back at them through our television or theater screens – but they’re not looking at us.

Back to Peg, as she is overjoyed to be – for one brief moment – acknowledged:

The reverse shot is another half-television / half-reality shot, similar to the earlier shot of the actors in front of the red curtain. Sellers is joking, and presented slightly off-center – as if he’s part of a shot / reverse-shot conversation between two individuals in the same space.

His father is slightly off center, as was Peg. They are the implied recipients of the conversation, and if the two shots are superimposed, we can see that Peg is slightly more to the center with his father occupying the opposite off-center point of the image of Sellers.

Peg is the more objective character – but why? The target of the conversation, if we are to believe the implied framing, is the father.

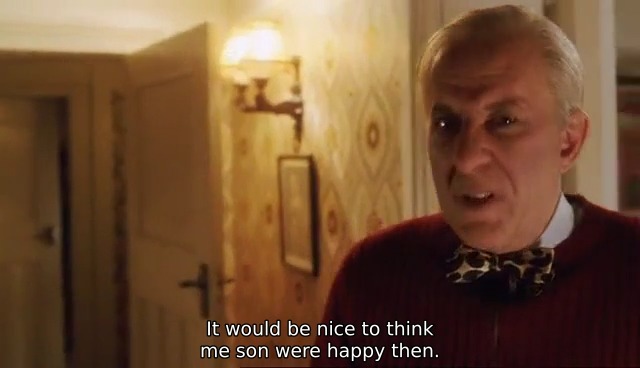

Back to the wider shot, so that we can see Peg ordering the father around. Note that the opening of the doorway creates a set of vertical thirds lines in which both characters are encased – although the father protrudes slightly futher outside:

Jump cut into Sellers’ father looking down at his mother …

… then down to the tray he’s picking up …

… then back up to his face for the beginning of a long tracking shot.

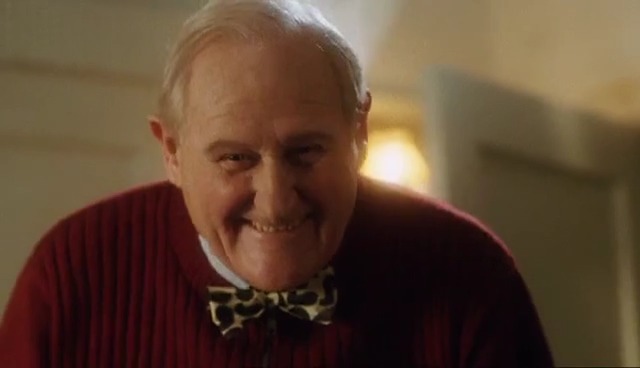

But wait. That’s not the father anymore. Through the use of a very subtle substitution, Sellers is now playing his own father:

He begins to address the audience directly:

It is being done with the voice of the father and the clothes of the father, but we are very aware that it is Sellers playing his own father. Is our narrator Sellers, wearing the visage of his father, or is it the father, with the film using a particular expository narrative technique? I tend towards the former explanation.

The shot / reverse-shot setup of showing Sellers across from his father was an interesting choice, as Sellers ends up essentially inhabiting his father’s form to talk directly to the audience. The father is continuing an unspoken conversation with his son – but the son insists on carrying on both sides of the conversation, as far as we are concerned.

The wider framing of the father and the mother foreshadows the breaking out of the epistemological framing by showing the father breaking out of the confining frame and presenting him as the primary source of interest by both having him stand (appearing taller than the mother, who is sitting) and having him staged closer to the camera – allowing perspective to subtly associate him with more importance. The part of this that isn’t foreshadowed, however, is that Sellers will be taking the place of the father in the spotlight ; it’s almost as if he can’t bear for another to have a turn in the spotlight.

He walks out of the room, which we can now see is a set.

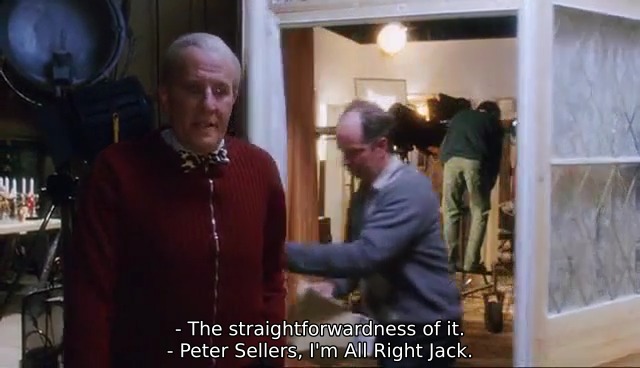

We’re given a view of very obvious set components – nothing is said, but rather implied, as we see crew members and equipment shuffle past him:

Now things get a little more tangled. We can hear voices of the awards ceremony on the television as he walks by the opening to the set which the father character had just inhabited.

The father tells a story, expositorily relevant to the subsequent scene. We pull in on his face – assuming that we’re going to learn some hidden truth about Sellers.

As we’re fed that last nugget of information, the camera swings down towards the floor …

… to focus on people walking by a discarded object.

And we jump cut to the next scene by showing a similar angle with a crowd of people walking.

Fasten your seatbelts, we have returned to the main epistemology of the film.

Retconning your own life

For the second scene, we’re starting with the “end” of the scene in which Sellers’ first wife leaves him.

They sit at thirds, with a palpable negative space between them.

She tilts her head in, so that their foreheads are touching:

Then a wide of them, off-center, in a trashed apartment. It should be noted that the two of them are the straighted vertical lines in the shot – and that Sellers was the one who trashed the apartment. He has created the metaphor for their relationship intentionally.

Sellers is in frame with her as she walks away…

… and we reframe to pull him in closer as she is excluded from the frame. He is presented off center, staring past us at his soon-to-be-ex-wife.

His wife reaches the door. Keep this shot in mind, as we’re going to see a very similar one in a few moments.

She turns around to deliver a final barb, a reference to his mock suicide attempt …

And we pull away from Sellers, in the ruins of his marriage.

Remember that shot of his wife against the door? We see virtually the same shot against the other side of the door, except that she is more centered.

And the epistemological transition has occurred. We’re now in another layer of the film, as we see a crew member walk by and hear “cut!”

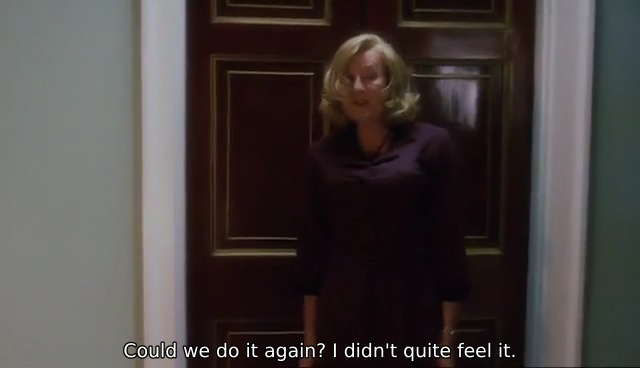

Except that it’s not the actress playing his wife – it’s Sellers, dressed and made up to look like her. He’s not addressing the audience, but we are instead seeing him as her on the film set, interacting with the members of the crew.

“She” is led into an ADR booth …

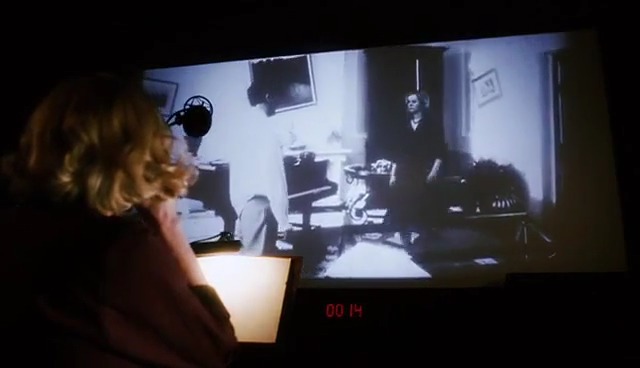

… where she sees a black-and-white rendition of the scene we have just witnessed, with the “wife” superimposed in color in front.

But now we know it’s Sellers. He is effectively retconning the end of his failed marriage by saying what he would have liked his wife to have said.

The second half of the last line shows the actual wife on the screen as we saw her, but in black and white.

Back to Sellers, occupying the same position in the frame as the image of the wife, but re-assuming frontality for the purposes of narration.

We see the playback of the film continue …

… and cut to the actual continuity of the film, in color, as Sellers runs with his tail between his legs back to his parents, after the failure of the marriage:

It didn’t change anything. Even though we see the Sellers character attempt to change the epistemology of his reality in the film, he cannot. His character is seen to jump in and out of his reality – but never as himself.

Whose film / life are we in, anyway – and who is this “Peter Sellers”?

The last sequence to examine in this article is a sequence where Sellers is traveling in the backseat of a car with Stanley Kubrick, attempting to perfect Major Kong’s Southern accent for Dr Strangelove.

We establish that we are, indeed, moving down a street in a car.

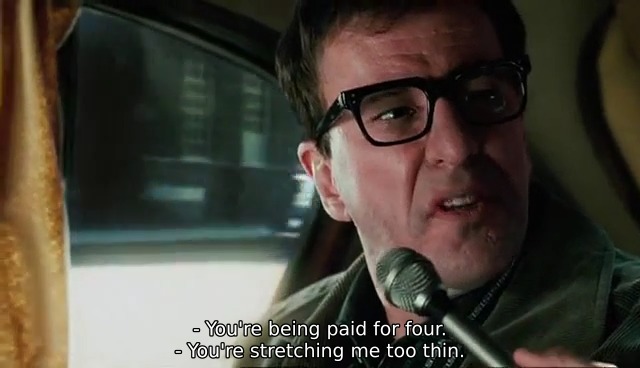

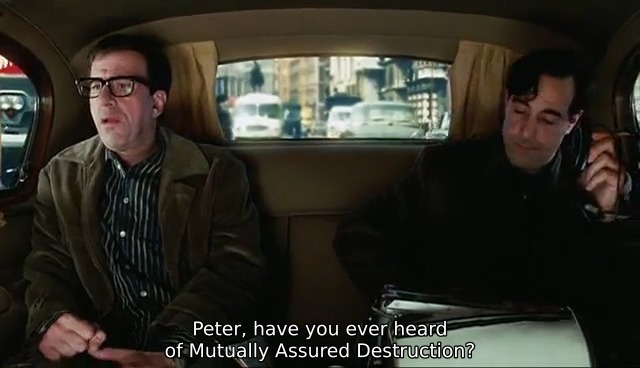

Then a two shot of Sellers and Kubrick in the backseat. Each man occupies their own third, with Kubrick’s arm crossing both thirds lines to intrude into Sellers’ space.

Shot / reverse-shot:

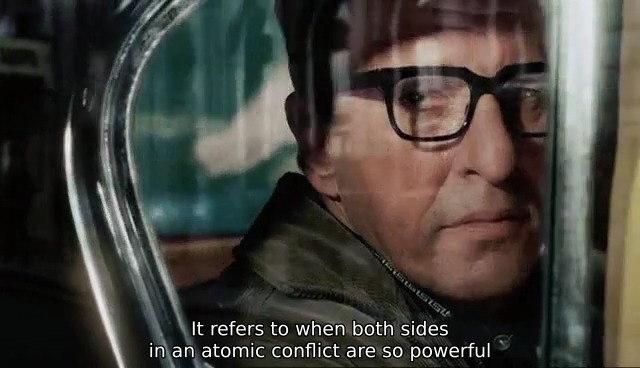

… followed by a two-shot so that Kubrick can explain his MAD metaphor …

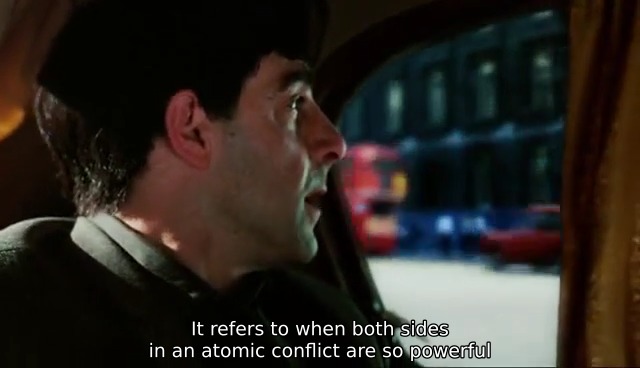

… back into the shot / reverse-shot rhythm.

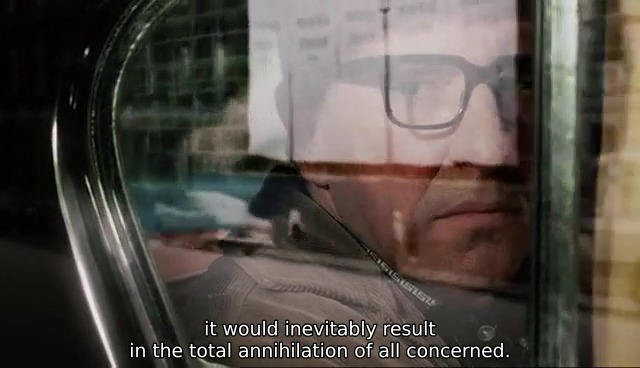

Except that we move outside of the car. Both Sellers and Kubrick are viewed through glass, with reflections dancing in front of them as they move down the street:

Sellers has had enough of the conversation and says that he’s “getting out”. The car is, according to us, still perceivably in motion.

He crosses in front of Kubrick …

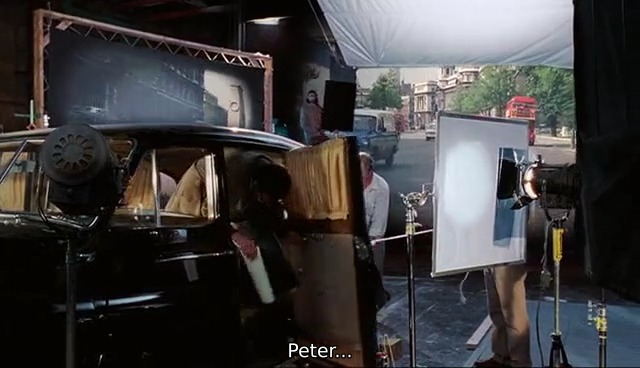

… and we reveal the back-projection and lighting setup which has been used to give the car the look of being in motion, surrounded by crew members:

We’ve crossed film layers, yet Kubrick, still in the car, has not. The conversation is continuing unabated as Sellers moves further and further away from the automobile set.

A quick series of long-lensed shot / reverse-shot cuts, to emphasize the separation between the two men:

We return to a shot from inside the car, with Sellers visible on the right edge of the screen, heading out of our view. Kubrick is pushed all the way to the left of the frame with his back to us.

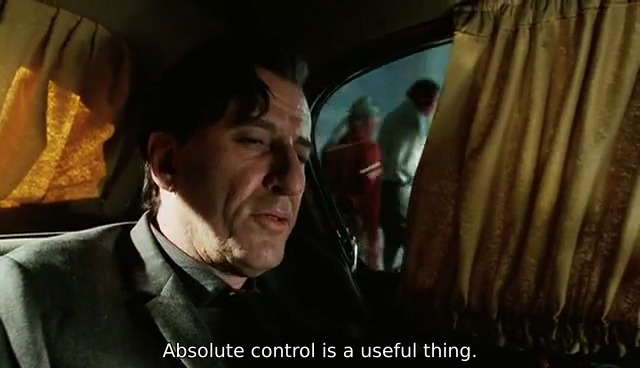

The camera pivots back into the car as the door closes, and we see that Kubrick isn’t Kubrick – it’s Sellers dressed as Kubrick …

… and acting as Kubrick.

The denouement of the scene is the single line which sums up the film’s take on the persona of Peter Sellers:

“This was a realization that Peter Sellers never had to face because there was no person there to begin with.”

Conclusion

When producing a biopic on an iconic character, incorporating epistemological shifts, rewrites, and corruptions to help emphasize that characters can be a very risky proposition – but Steven Hopkins et al managed to pull it off, in my estimation.

Internal conflicts and personality ambiguity are often conveyed through expository narrative dialogue, as it is the current trend in major films. However, it’s always better to show, rather than say, something. I find many similarities between the real biopic nature of The Life and Death of Peter Sellers and the fictional biopic of Deconstructing Harry because they both step outside of the standard epistemological construction of the film universe to allow both film technique and film structure to play a role in forming our perceptions of the characters.

A common post-modern / post-post-modern film technique involves consciously acknowledging the world-within-world nature of film in an attempt to either promote or subvert irony; these fail to have the same impact as Sellers because they aren’t intrinsic to the structure of the underlying idiom. We buy Harry and Sellers because the characters become more real to us through their ability to become larger than the epistemological universe around them.

(All images are presented under fair use guidelines – all frame grabs are property of HBO Films, BBC Films, Company Pictures, or any other entities who hold copyright on this film. They are presented for exclusively educational purposes.)