Dynamic range

Dynamic range, both as a literal and figurative concept.

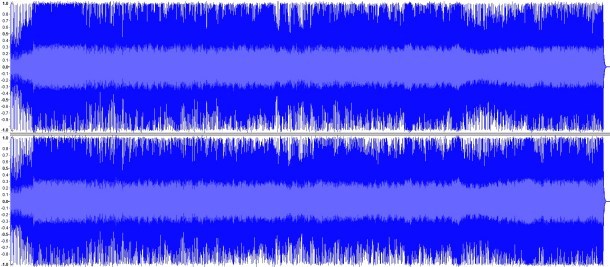

As a photographer or cinematographer, I’m sure you’ve come into contact with limitations in dynamic range. I have run into limitations with dynamic range in both the visual and audio field, since anything that involves “real world” signals is going to potentially run up against the ability of the digital mediums on which we rely to properly store the entire gamut of available analog data that we are able to perceive with our eyes and ears. To combat the loss of data, computer scientists and electrical engineers developed the process of dynamic range compression, which is usually referred to as simple “compression”. This reduces the gamut of presented information to a digitally representable format. There is, however, something which is lost – and that is the original dynamic range ; the amount of variance between the strongest and weakest signal. In small doses, or when done with finesse, this provides the ability to produce better sounding and better looking content in the digital realm. When overused, we see results like the loudness war.

I like to explore the more figurative aspects of many technical concepts, to which most avid readers of my work would attest. In that vein of ideas, consider the derivative concept of dynamics as a function of cinematic tension/resolution and feeling.

Much like a written work, cinematic works generally tend to follow a “plot/story arc”, which have a number of basic stages, even if the presentation, order, and presence will vary between works. As cinematographers, one of our jobs is to attempt to portray the basic plot elements, character interactions, and other potentially metaphysical aspects of the story through the lensing, lighting, focal points, composition, and method of stabilization and capture we use. (I’m aware that there are other control points, but forgive me my omissions for the sake of some semblence of brevity.) For example, for a more “cinéma vérité” style for a combat or heavy action sequence, a filmmaker could choose to shoot with less stabilization, looser composition, and less staged lighting, which would present the audience with the perception that the scene is far closer to the work of a documentarian than a staged film scene. In Saving Private Ryan, for example, the battle scenes have a decreased exposure time, resulting in action appearing far more caustic and (what we believe is) more realistic. This allows the relative dynamics of the scenes in question to be raised to allow far more tension and action to be shown, through simple camera work.

The issue with techniques like this begin to manifest themselves when they begin to flatten the dynamic of a film work through rampant and flagrant overuse. At some point, cinematographers realized that they could shoot entire films with these techniques, ostensibly to raise those tension and action levels to that same high. By doing this, they have effectively flattened the dynamic range of their works, producing an effectively and uniformly “loud” work. The questions that you might be asking are “why is this a bad thing, and why should I care?”

We view things as deltas, or differences. We understand happiness because we understand sadness, heat because we experience cold, and comfort and companionship because we can contrast it with loneliness. If the range we are give to deal with is only the “best parts”, we begin to lose our ability to appreciate it, and all of those things which should have made it special and artistic become mere convention. Think about it – if everyone screamed everything at the same volume, rather than having varying levels of emphasis and volume, wouldn’t that screaming have lost its impact and importance?

Every technique that you have as a cinematographer or photographer is another potential tool in your figurative tool box; but just because you have them doesn’t mean that you have to use one particular one all the time. Handheld camerawork has its place, and even though modern technology has provided many methods of stabilizing camera and lens motion, from the steadicam to image stabilization/vibration reduction lens to three point shoulder rigs, we still find many cinematographers intentionally introducing shake into their footage. I wrote an entire essay on the importance of stabilization, so I won’t reiterate my grievances here.

It’s important to understand why you’re doing something rather than simply doing it for convenience or convention. If you’re using a wide open aperture, are you doing it because you’re having lighting issues, or simply because you think that everything should be shot with the thinnest DOF possible? Is there some sort of artistic reason why you chose to shoot with a 24mm vs a 35mm lens for a particular shot? Are you using a tripod-based shot rather than a steadicam for a reason? Asking questions and analyzing your own work, as well as the work of others, is key to artistic growth, as well as understanding how to use your skillset as a photographer or cinematographer.

I am, by no means, at the top of the skill grouping for photography or cinematography. Many of the entries I have authored here are products of making mistakes, and they are the attempt I am making to keep others from having to make some of the very same mistakes I have made. Even films and other work which we don’t particularly like as a whole may have a few setups or shots which provide food for thought. So, watch those films with a critical eye, and hopefully we can all expand our “toolboxes”, as well as learn how to use them in a more effective manner. Good luck!