Layers, the Inner Film, and Reality

Looking at film within film; stories within stories.

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage, and then is heard no more. It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. - Macbeth, Shakespeare

We’ve become accustomed to viewing film, whether consciously or subconsciously, as a separate world with its own intrinsic epistemology. It represents a false world constructed within our own world – much like a play or other piece of narrative fiction.

Certain films exhibit a layering of realities – a “film within a film”, or “mise en abyme” – which can be used as a powerful narrative tool or as a metaphor for some larger concept. By interweaving stories within stories, a more complex tale can emerge which can be more intricate than the stories would be if told separately.

Stories within Stories: Flashbacks and Narration

Layered stories don’t have to represent a separate reality or epistemology ; they can also be used as an expository tool. In Zemeckis’ Forrest Gump, the vast majority of the story is told as a series of flashbacks – which we can view as being self-contained short films, even though they exist within the epistemological domain of the film. We believe the stories that we are being told are objective reality, even through the denouement, because we are given no reason to doubt the sincerity and authenticity of our venerable narrator at any point during the film.

The concept of “narrator as liar”, which I have explored, along with the layered story concept, in my original piece on film epistemology, shows that the concept of a sincere and authentic narrator can be subverted to use flashback sequences and narration as both a narrative tool and a plot device. The examples I had given included Verbal Kint in Singer’s The Usual Suspects and the narrator in Fincher’s Fight Club.

There is an additional aspect, along with a component of ambiguity present in American Psycho, in that that Bateman’s “inner story” continues with the “narrator as liar” concept during the natural time-flow of the film, without resorting to flashback sequences to tell the ambiguous portions of the story. It should be noted that, while there are non-temporal flow portions of the story told through flashbacks, they are not a majority of the device used to tell the story. We’re treated to the ambiguity of a narrator who doesn’t know that he is a liar, much like the narrator in Fight Club – but Fight Club is told, almost entirely, as a series of flashback sequences.

Putting aside “narrator as liar” examples, however, shows that many Hollywood films rely heavily on flashback-style authentic exposition to tell their stories within their epistemological system; so much that we don’t view those flashbacks as a potentially separate epistemological system or inner story, but as an adjunct to the primary story. In this way, we are told stories within stories without them actually being a logically separate story.

Stories within Stories: Stages, Films, and an Inner Story

Inner stories can be represented by actual film, theater, or book productions or materials. In this way, the inner story can be physically separated from the outer story – even if some ambiguity is potentially introduced in the story about that separation.

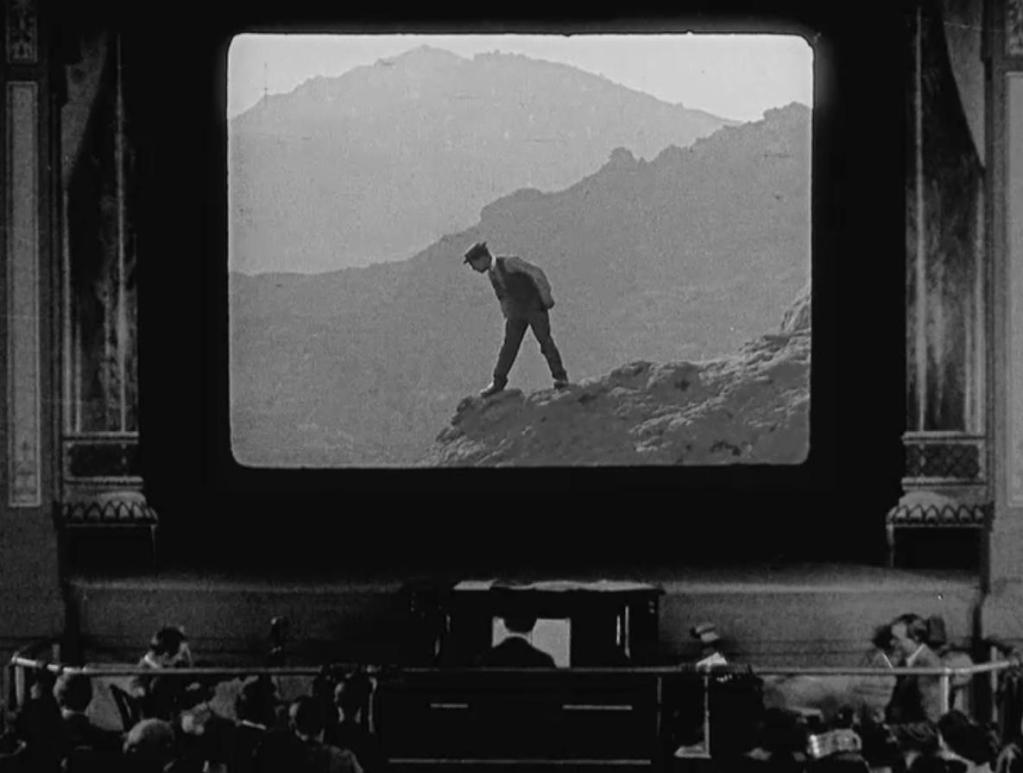

Keaton inhabiting the inner story in 'Sherlock Jr'

Keaton inhabiting the inner story in 'Sherlock Jr'

Keaton’s Sherlock Jr tells the majority of the narrative through the dream of the protagonist, who works as a film projectionist. This, by itself, isn’t anything special, but Keaton’s character walks through film audience present in the outer story, who are implicitly watching the inner story, and physically injects himself into the film by walking through the invisible “fourth wall” to be come a part of the inner story.

Weir’s The Truman Show treats us to an unwitting participant in a television show, in what appears to be an allegory about man’s relationship to his creator as he discovers the true nature of his existence. Where it was a bit heavy-handed in some places (Harris’s character being named “Christof”, or the line “I am the creator … (pregnant pause) … of a television show”), the “real world” and outer story exist outside of the inner story while the denizens of the outer story are shown voyeuristically watching the predominant inner story as it slowly is shown to recede into the outer story as the metaphoric curtain is pulled back. Our protagonist literally bows before leaving the not-so-metaphoric stage, giving us a curtain call for the inner story moments before the outer story ends. There is also a certain implication that Truman is experiencing a widening of his perceptions and metaphorically (as well as physically) escaping the epistemological confinement in which he lived his entire life – quite possibly a not-so-subtle poke at religion.

I refer back to one of my favorite Gilliam films, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen for an example of an inner theatre-stage-set story, as well as to Iñárritu’s now critically-acclaimed Birdman. Both have an inner theater production which relates (to one degree or another) to the outer story. I’m not going to even attempt to do a better technical analysis of the film than SEK did, but I would like to note that both the inner stage play and the meta-discussion in the outer story regarding that inner play relate back to the outer plot and outer reality, even as the protagonist appears to be losing his grip on it. Theater has been used in other popular films, more recently Moulin Rouge and both versions of To Be or Not To Be, although it does not inherently contain the same implications about the nature of reality that Munchausen does; the concept of mise en abysme is, instead, used as a simple narrative device to drive the story forward.

As for a literature-based inner story, Goldman and Reiner’s The Princess Bride qualifies as an example of an inner story told as an outer story narrator relating the contents of an outer story work of fiction containing the inner story. A far more nuanced example of this would be Kaufmann and Jonze’s Adaptation because it defies that simple categorization. Even though Hollywood films’ authors have become increasingly self-referential – possibly due to the old adage about writing “what you know” (which is, appropriately, lampshaded in Adaptation through Brian Cox’s character) – most of the stories are banal tales of narcissism and self indulgence, as the author almost invariably makes him or herself the infallible protagonist.

Ambiguity Between Inner and Outer Story

In Adaptation, Kaufmann’s inner story starts by intentionally confusing the real world with the outer story. This trend continues throughout the course of the film, and was so successful at confusing the intended epistemology that a fictional character, Kaufmann’s twin brother, received a joint writing award for the screenplay for Adaptation. He also creates an inner story as the screenplay adaptation for “The Orchid Thief” – which is a real book in our reality, and which serves as the real world source for the story material in Adaptation. The outer story is an adaptation of “The Orchid Thief”, but so is the inner story. It is a masterpiece of both ambiguous epistemic domains and an interesting viewpoint regarding the entire craft behind film adaptations.

Well, I really want to encourage a kind of fantasy, a kind of magic. I love the term magic realism, whoever invented it — I do actually like it because it says certain things. It’s about expanding how you see the world. I think we live in an age where we’re just hammered, hammered to think this is what the world is. Television’s saying, everything’s saying “That’s the world.” And it’s not the world. The world is a million possible things. - Terry Gilliam, Salman Rushdie talks with Terry Gilliam (cite)

I would be doing any readers of this piece a serious disservice by failing to mention Terry Gilliam’s works in a piece regarding inner and outer story ambiguities. Most of his films have some sort of delusion, story, or narrative work which tries to transcend the barrier between imagination and reality – of inner story and outer story.

Munchausen delivers this ambiguity through both filmmaking techniques, such as cross-cutting quickly between two conflicting layers of story (the bombing of the theater contrasted with the escape from the Sultan’s palace) or mixing sets in such a way to deliberately fuse the stories together (when the actor playing the Sultan is pushed out onto the stage for the reveal that he is now in the Sultan’s palace). The battle between imagination and reality is given a physical form, as well, through the characters of The Right Ordinary Horatio Jackson (Jonathan Pryce) and the Baron himself. In one of the inner stories, Jackson assassinates the Baron as he is being accepted and lauded by a world which had rejected him – but it is shown to be an inner story, and the Baron (imagination) is still able to outlive and outwit Jackson (reality).

A similar, yet different, scenario is set up in Twelve Monkeys. Cole has a recurring dream about seeing a man shot before he returns to the past – but is the “past” really the present, and his “present” (our future) really just a delusion? Gilliam spends a good portion of the film playing up the ambiguity of those two states against Cole’s fragile mental state. We’re given some sort of epistemic relief when Dr Railly finds pictures of Cole in a history book and identifies a bullet as being very old – but there’s never really any certainty, and the ambiguity can theoretically continue on. Cole’s “dream” is revealed in the final act to be his unknowing memory of his own death, completing his timeline in an out-of-sequence circle. Even though Cole is warned that he will be lost to the past (assuming that his “present” is actually reality) and told that history is immutable, he still tries to change it. We are all puppets in the grand scheme of history – from an anthropological point of view, this has already happened – but Cole can’t accept that he is not the master of his own destiny.

Another example of ambiguity between outer and inner story / film is Brooks’ Blazing Saddles. Not only do the characters seem to be periodically aware that they are part of the outer film, occasionally using frontality to speak directly to the audience a la Groucho Marx, but the outer film is the inner film. Much as he did in Spaceballs, Brooks conflates the inner and outer films while making it clear that the characters are somewhat aware that they exist within a film. Spaceballs does this through both dialogue (“The ship’s too big; if I walk, the movie’ll be over.”) and through entire scenes (the “instant cassettes” scene). Although this is primarily played for laughs, it intrinsically changes our perceptions of the characters through our knowledge of their self-aware nature. Blazing Saddles not only juxtaposes the ending fight scene in Rock Ridge with the characters literally breaking the fourth wall into other sets, but has the characters simultaneously watching their film while other characters are, according to the in-universe continuity, still making that film. Continuity even carries over between the two layers, with Wilder holding his theater popcorn bucket in the scene after he is shown to be in a theater … watching the very film that he has yet to finish.

The last example I’d like to cite is the excellent The Life and Death of Peter Sellers. It follows an interwoven narrative, given with subjective exposition by the titular character, played expertly by the always-superb Geoffrey Rush. The story within story motif is clear as Sellers is shown intermittently to be playing every character whenever the thin curtain between the outer and inner material is pulled back. The titular character is so egotistical and full of himself that we are constantly reminded that we are seeing the world through his subjective gaze. We have to assume that what we are seeing somewhat resembles the objective truth, even though our narrator is a self-proclaimed liar, to one degree or another. Apart from Rush playing Sellers playing his characters as a function of narcissism, it functions as a film technique to point to Sellers’ lack of a solid sense of self or personality – much as the discontinuous editing technique of Deconstructing Harry points to the fractured way that its eponymous character views reality.

Reality as a Shared Delusion

Even though the Wachowskis’ The Matrix popularized this in film culture, the idea that reality as we know it is just a shared delusion has been around for a while. John Carpenter’s They Live insinuated, more than ten years before The Matrix, that most people live in a shared delusion, unable to see the reality that exists around them. The inner story and the outer story share not only diegetic space, but also epistemological space. They live in the same world, even if the shared delusion of some make it appear to be a different world. The campy pastiche film The Adventures of Buckaroo Bonzai Across the 8th Dimension (which predated They Live by four years) uses a similar separation between inner and outer story. It does use a different differentiation mechanism: a spark of energy rather than a pair of sunglasses. (I compared them in this piece on hidden truths.)

The Matrix physically separated the denizens of the shared delusion by embedding the inner story in the container of a computer simulation, which the outer story characters, once aware, could jump in and out of. It played very heavily off of the concept of awareness, in that some people in the inner story could jump to the outer story by having knowledge that they were essentially characters in a fiction. There are a lot of philosophical overtones present, and I’m sure others have done far more justice to analyzing them than I would have done.

Proyas’s Dark City is an interesting hybrid between the type of shared delusions in They Live and The Matrix. Like They Live, the characters experiencing the shared delusion of the inner story share the same space as the characters experiencing the outer story, and much like The Matrix, they are unwitting test subjects, whose gruesome reality is not apparent to them until they are willing to take a leap of faith, of sorts (the red pill/blue pill test in The Matrix and trying to find Shell Beach in Dark City). In Dark City, no one questions why there is never any sun, nor why they never have any desire to leave the city, nor why they only have dim, distant memories; they accept the reality with which they are presented.

Nolan’s Inception not only has a inner story, but three more story layers beneath. One of the criticisms I’ve heard about Inception was that, due to the varying story layers, it was difficult to follow; I didn’t agree with that assessment, but felt compelled to include it here. Depending on whether or not you agree that the “real world” shown as the outer story layer is, indeed, the outer story layer or not, there may be an unseen layer between the further visible story layer and our reality. To further complicate matters, the characters are all meant to represent different functions of filmmakers – there is a “meta-meaning” on top of the already convoluted layered-reality story line. One of the most important epistemological constants in all of the realities is that the inhabitants of any of these stories are, much like the characters in most films, unaware that they are living in a story, or a story within a story, or a story within a story within …

Much like Dark City’s theme of the Strangers trying to steal our souls / humanity through our memories, Jeunet’s La cité des enfants perdus centers around the theme of a mad scientist, Krank, trying to take youth / life from children by stealing their dreams. The film is rife with shared delusions and obsessions, from the clones’ attempt to prove which is “l’originale”, to Krank’s obsession with living through the dreams of others, to One’s need for family to live out his dystopian existence.

Why does this technique resonate with us?

I don’t think I can put forth a concrete answer to that, mostly due to the way that eisegesis trumps exegesis in the majority of film viewers.

My working theory is that layered stories resonate because they tap into some subconscious desire for us to see this world as as dream – or at the very least, a part of a bigger, better world. To quote:

There’s an old joke - um… two elderly women are at a Catskill mountain resort, and one of ’em says, “Boy, the food at this place is really terrible.” The other one says, “Yeah, I know; and such small portions.” Well, that’s essentially how I feel about life - full of loneliness, and misery, and suffering, and unhappiness, and it’s all over much too quickly." - Annie Hall, Woody Allen

This desire for more – of something – generally is accompanied with the idea that the something we seek is better than what we have here and now. Film is, to one extent or another, escapism. It could be argued that one of the pushes for epistemic closure in film stems from our desire not to let the comforting delusion of the film universe, which we love, abruptly end with a credit roll.

There are some films where the story breaks out of an inner world into an outer one, and the outer world is far more horrifying and bleak than the inner world. This subverts our desires for a better outer world, as exploited masterfully in Proyas’s Dark City and the Wachowskis’ The Matrix. It is also implied in The Truman Show that the outer world is a terrible place, by Christof.

References

- Coste, Pier: Narrative Levels

- McIntyre: Point of View in Plays: A Cognitive Stylistic Approach to Viewpoint in Drama

- Wikipedia: Deictic Field and Narration