The Departed: Introducing Costello and Life in the Shadows

Examining the introduction of Frank Costello in The Departed

Scorsese’s The Departed netted the venerable director his second “Best Director” Academy Award and only his first “Best Picture” Academy Award in his entire 20+ year career, despite being a remake of another film.

Many film critics and scholars have examined the film’s themes and visuals, but I would like to concentrate on a single character’s introduction and early visualization on the screen: Nicholson’s Frank Costello.

We first encounter Frank Costello as a disembodied voice, expounding on existential topics over vintage news footage.

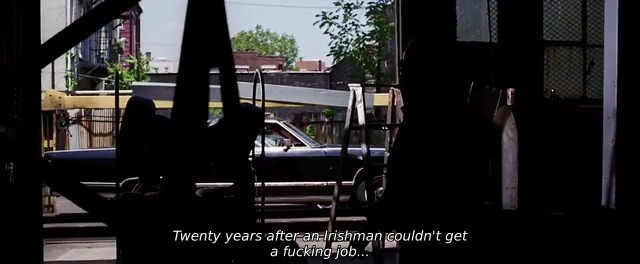

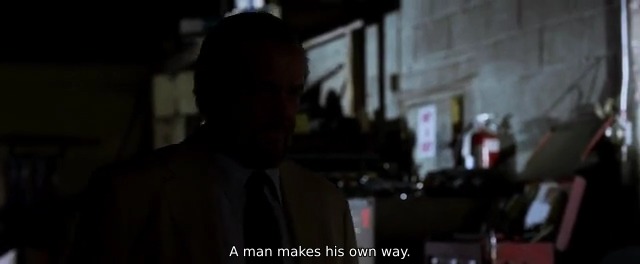

The first time we actually see him is when he starts a slow walk, in the shadow of a shop with open car bays, from the right to left side of the frame.

He appears almost exclusively as a silhouette, with virtually no color present in his face or clothing.

As the shot progresses, the camera dollies from right to left, along with him, but we only catch slight reflections of his glasses. There should be some light hitting him, but there isn’t. This is the midpoint of the shot, where he hits center frame.

He delivers his final line of the shot as he begins to drop off the left side of the frame, and out of our purview.

Already we know a few things about the character through his basic exposition and accent (as well as the “Boston” placard in the introductory sequence), but the director’s choice in keeping this character completely shadowed during his introduction speaks more to his nature than another thirty seconds or minute of monologue could. The right-to-left motion of both the camera and Costello offer subtext to indicate that he is not a good person, and is moving against the natural order of things. We generally expect logical progressions on screen to occur from left to right, which indicate progress, but Scorsese is subverting this by having his character purposefully walk against that directionality.

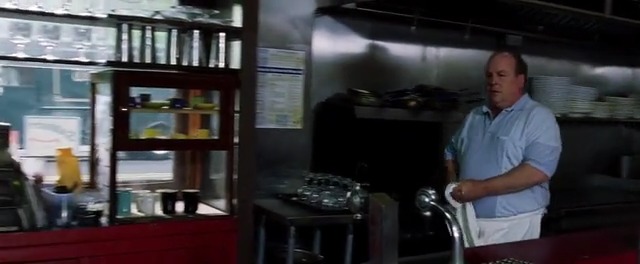

The next shot is a wide shot of the exterior of a small store / bodega, and the camera sweeps in to show us the store clerk working behind the counter. There’s nothing special to see here, right?

Wrong. We pan back to the left (notice that subtle directionality again), and Costello is there. He isn’t fully shadowed, but his back is to the camera, so we can’t see his face at all.

The most detail we get of him is his hands in a closeup, exchanging money with the cashier. It’s not immediately apparent when we first see the cashier going for the drawer that Costello is extorting him until the dialogue backs it up …

… in the wider two-shot. The cashier is almost exactly on the rightmost thirds line in the frame, but Costello is skewed off to the left of the frame, and inexplicably masked in darkness. We can see his face – somewhat – but it’s not clear.

Even the medium shot of Costello doesn’t offer us much in terms of detail. He’s still mostly locked off in the left third of the frame, with only his arm and a sliver of his face making it into the rest.

When Sullivan’s younger self is revealed, sitting down, Costello and Sullivan are represented at thirds, and we can see that there’s light everywhere …

… but not on Costello. Even up close:

Sullivan, as he starts out on his path with Costello, heads off to the left. He’s even seen leaving Costello behind, in the shadows, on the right.

We’ve just been given a window into the hierarchy of good and evil in The Departed, even if we might not consciously know it upon first viewing. When we pick back up with Sullivan and Costello, the protégé occupies center frame as Costello paces in the shadows, elucidating his views on the roles of good and evil in society.

Costello is, again, the only one in the shadows. He’s almost supernaturally shadowed, as everyone else seems plainly visible.

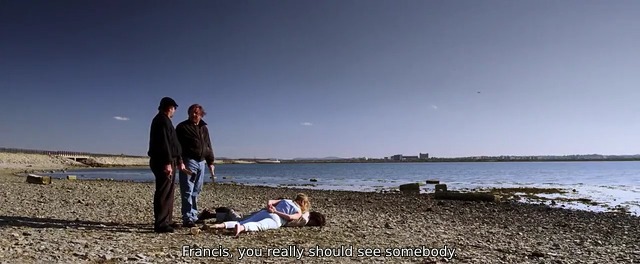

Even in the middle of a sunny day, in the first of the film’s pertinent flashback sequences, Frank has little to no light on his face. He’s also still occupying the left side of the frame.

Cut back to a wider shot, and he’s still on the left, even if only by a very small amount. His face is turned away from us, so we’re denied a full-on glimpse of his visage during this flashback.

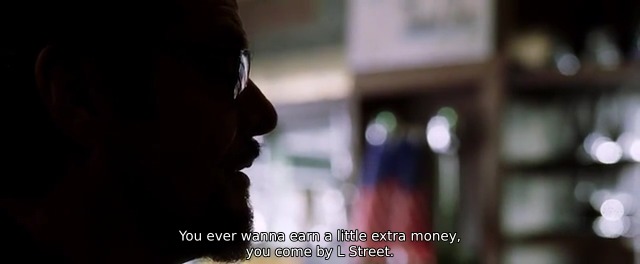

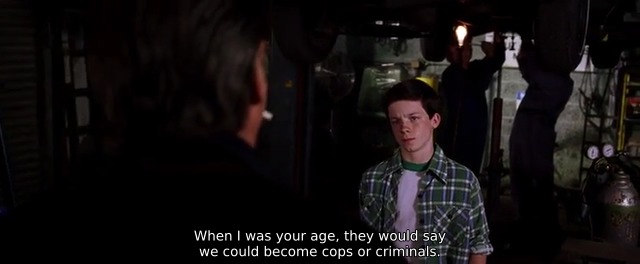

Back to the garage, we see Sullivan’s face over Costello’s shoulder as he literally looks up to this man.

But, for the final act of his introduction – comprising the most salient point of his long monologue – he starts in the shadows …

… begins to come out as he sets up his point …

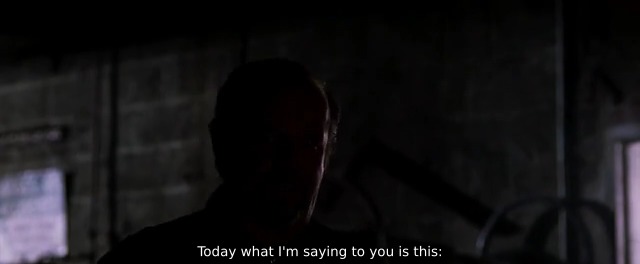

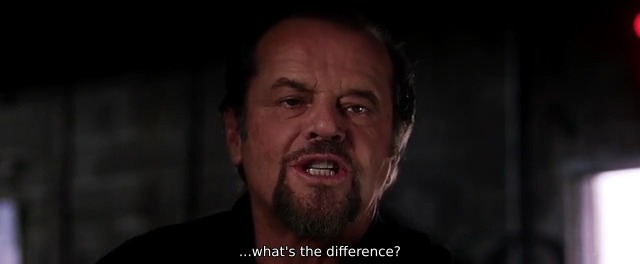

… and is revealed when he asks “what’s the difference” between being a cop or being a criminal.

The gravity of this reveal is absolutely intrinsic to the plot of the film, as Costello is more or less both, being an FBI informant (revealed much later in the film), as well as being one of the most violent and wanted criminals in Boston. He doesn’t see a difference because, for him, there is none, as his true self is revealed.

It is also key in the dual plot threads of criminal pretending to be cop (Sullivan) and cop pretending to be criminal (Costigan) which make up the majority of the film.

One important take-away is that what you don’t see and don’t know can be as important, if not more important, than what you do see and do know. Withholding Costello from us fully for about five minutes means that his introduction is going to mean much more to us, both in how it is done (emerging from the shadows) and when it is done (the context of his speech).

(All images are presented under fair use guidelines – all frame grabs are property of Warner Brothers, Plan B Entertainment, Initial Entertainment Group (IEG), or any other entities who hold copyright on this film. They are presented for exclusively educational purposes.)