They Live vs Buckaroo Bonzai: Exposing the hidden truth

Comparing the exposition of hidden truths in They Live and The Adventures of Buckaroo Bonzai Across the Eighth Dimension

If you were asked what John Carpenter’s They Live had in common with the campy 1980s sci-fi pastiche The Adventures of Buckaroo Bonzai Across the Eight Dimension, the first answer to come to mind might have something to do with aliens; I’m going to examine the way that a hidden truth, or additional story/film layer is exposed to some characters within the epistemic system of a film.

NOTE: I’m aware that The Matrix also deals with hidden truths, but it involves a separate physical layer of the story/film.

The Adventures of Buckaroo Bonzai Across the Eighth Dimension

Quick! Check the angular vector of the moon! - Hans Zarkov, Flash Gordon

This film is a delightfully polarizing work; people either seem to recognize it as a clever pastiche of alien-themed sci-fi and action/adventure films, or they just hate it. One of the things that really sold me on Bonzai is how the Renaissance Man protagonist, played by Peter Weller, never seems to be in on the joke. He plays the role with a level of seriousness which rivals the way Topol played Hans Zarkov in the cult-classic-level-of-awful 1980s Flash Gordon.

The hidden truth is that aliens walk among us – both good and bad – which can only be seen with a bio-electric spark, passed from person to person by touch (or by a phone call). The introduction of this mechanism comes during a press conference, where Buckaroo Bonzai is explaining how he drove through a mountain with the use of the film’s MacGuffin, the “oscillation overthruster”.

As the press conference starts, we see two men in ill-fitting suits sitting down in the middle of the conference.

Bonzai is informed that he has a call from “The President”, which is magically being re-routed to a phone booth down the hall.

He tries to answer, but the line is full of static …

… because there are Black Lectroids on the other end of the call, orbiting the earth in something which looks like a really nasty kidney stone.

Bonzai closes the phone booth door to hear the phone call better. This is somewhat comical, as there are no sounds in the hallway – but he is now visually separate from the others, confined in the phone booth.

ZZAAAPPP! A nasty-looking spark hits Bonzai in the ear, and he falls out of the phone booth.

Rawhide tells everyone not to touch Bonzai, as he writhes around on the floor.

In what is the most puzzling part of this entire sequence (at the time – we find out later what he’s doing), Bonzai begins to write on his hand …

… and then bursts out onto the stage, wild-eyed …

… and pulls the Zarkov hero pose to proclaim his hero lines. Notice that Weller, our hero, is comically shorter than both Rawhide and New Jersey. The camera pulls in towards Weller, pushing everyone else out of the frame. They’re obviously concerned about their leader, but Goldblum’s New Jersey shows a level of confusion on his face that indicates that it’s the historical aspects of Bonzai’s character which are causing his allegiance – he doesn’t see what Bonzai sees.

Bonzai: “There they are! Don’t you see them?”

Rawhide: “What do you mean?”

Bonzai: “EVIL! PURE AND SIMPLE – FROM THE EIGHTH DIMENSION!”

The camera has deliberately not shown the subject of this outrage – we have to wait.

We then see a dolly in / zoom out shot which is very similar to the original static shot of the two men sitting down, but we now see with Bonzai’s eyes – they aren’t what they originally appeared to be:

They Live

John Carpenter’s They Live is a completely different beast. It attained cult status after it critiqued Reaganomics and racial divides, and was mysteriously removed from theaters after a spate of popularity.

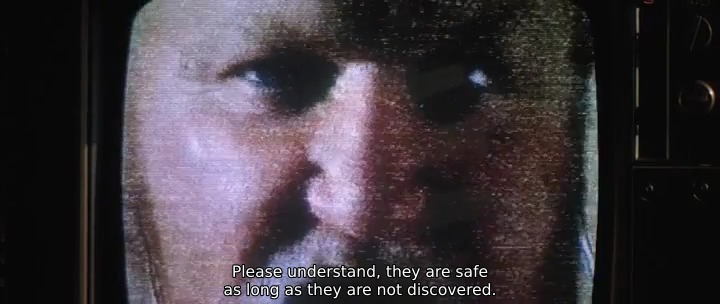

We’re introduced to the source of our MacGuffin perceptual device through a group of rebels, broadcasting a pirate television broadcast to try to disperse their message to the masses – but to no avail.

After their compound / building is stormed by police, “Nada”, our nameless protagonist, goes back in to surveil the damage.

He kicks a panel in the wall …

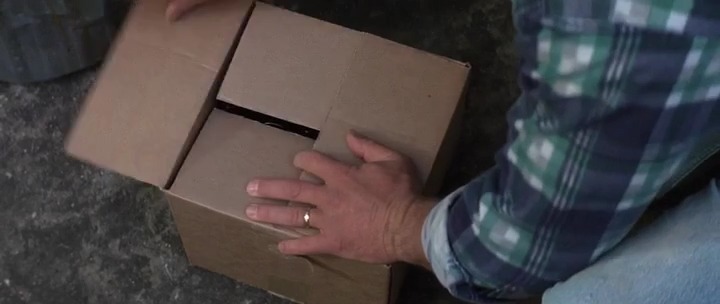

… to reveal a hidden compartment, containing a mysterious box.

Nada absconds with the box, after hearing police sirens. Notice that he’s not pictured in the same frame with any other person. We’re very aware that it’s him and whatever is in the box.

He finds an alcove, filled with the discarded refuse of a world to which he does not belong. He, like the trash, has been discarded and marginalized by society. All of the color in this shot is relegated to the space inside the gap in the wall.

Nada haphazardly tears the box open…

Shit. it’s just sunglasses. The truth is, apparently ordinary.

A reaction – Nada is confused; why would these rebels give up their lives to protect a box of sunglasses?

He digs to see if something is hidden. He is looking for the hidden truth, quite literally.

We’re back to the reaction, but wider. Nada is still isolated, but further from any sort of revelation ; it’s almost as if we’re pulling away from being inside his head.

Erring on the side of caution, Nada buries the box in the bottom of the trash barrel next to him.

He finds a solitary pair of sunglasses on the ground, and decides to hell with it and pockets the item.

It should be noted that, all throughout this sequence, Nada says nothing. Every bit of exposition we receive in this sequence is done in a complete dialogue blackout.

Cut to Nada walking down the street. Everyone else is wearing plain, solid clothes, whereas he is dressed in a working-class plaid shirt and jeans. We can see the sunglasses dangling from his left hand.

Apparently, he’s poor enough to be unable to afford sunglasses, so they go on.

But the grate on the sidewalk surface seems to be in black and white. He takes the glasses off, then stops. We cut in close to see him put them back on:

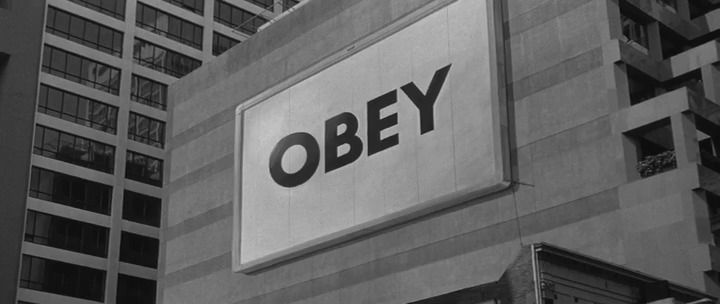

We then see the reverse shot – what Nada sees – and it’s a horrifying stark black and white message to OBEY.

He takes the glasses off, and we see a perfect superimposition of what everyone else sees:

Reverse again – and the realization of the hidden truth hits him.

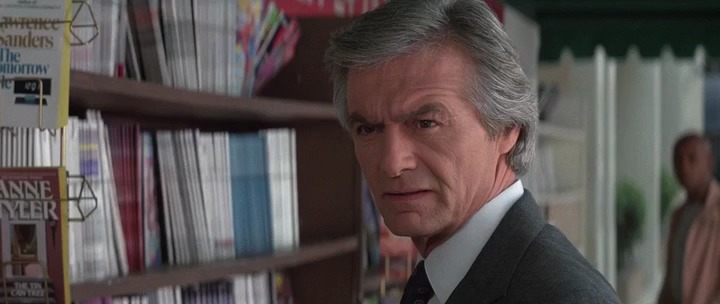

When he sees a man in a suit at a newsstand …

… the glasses show him a completely different story.

The view of the alien with the glasses on is taken with a much shallower depth-of-field; the truth is far more important than the unimportant doldrums of the rest of reality.

Comparison

The hidden truths in these films are superficially similar : Bonzai revolves around a group of hidden aliens trying to manipulate and steal to return to their homeworld to conquer it, with retaliatory force threatening to destroy the Earth, and They Live centers around the idea that what we have now is the result of aliens having taken us over – without us knowing.

They both rely on a device – a spark or a pair of sunglasses – which unless used, allow the hidden evil forces to hide within plain sight. Both visually separate the protagonist to provide some mise-en-scène separation which allow us to subconsciously understand the virtual separate plane of perceptual existence on which our protagonists find themselves. Both have a certain amount of suspenseful built-up before the visual reveal of their respective hidden truths.

They differ significantly in their execution. Bonzai tends towards bombastic dialogue-centric exposition, whereas They Live tends towards slower (but more dramatic) implied exposition. Even though both contrast the subjective view of the protagonist (paradoxically showing the objective reality which is invisible to those around them), with the theoretically objective reality of those around them (which is subjectively wrong in the larger epistemic reality which the others are not aware), They Live juxtaposes the images closer together for theoretically more visceral impact without the crutch of revealing dialogue. Bonzai separates the false view and true view of the aliens by more than a minute of film time, which makes the transition less easy to comprehend – and the MacGuffin less obvious.

They Live exploits both production and costume design to visually separate its protagonist from the unknowing masses, as well as a narrow depth of field. This far more subtle separation seems to play better for me for tension – but Bonzai is playing for laughs, so it may not be a fair comparison.

In both films, the inner mechanism of societal separation is played out through externally visible means because we can’t look inside of a character – but they both construct point of view shots to try to help us see through their protagonists’ eyes.

(All images are presented under fair use guidelines – all frame grabs are property of Sherwood Productions, Alive Films, Larry Franco Productions, or any other entities who hold copyright on this film. They are presented for exclusively educational purposes.)