Smoke: The Art of the Long Take

Examining 1995's Smoke and its use of the long take

“I’ll tell you what – Buy me lunch, my friend, and I’ll tell you the best Christmas story you ever heard. How’s that? And I guarantee, every word if it is true.” - Auggie

Smoke is Wayne Wang and Paul Aster’s first collaboration on a serendipitous independent film, to be followed up by the less-successful Blue in the Face. I’d like to examine an extremely long take in the third act of the film, and the way it helps tell the film’s story.

This scene, between Paul Benjamin (William Hurt) and Auggie (Harvey Keitel) clocks in at about 11 1/2 minutes, with the single longest take clocking in at about 4 3/4 minutes.

Auggie has promised to tell Benjamin “the best Christmas story you ever heard”, and we open on them sitting down for lunch.

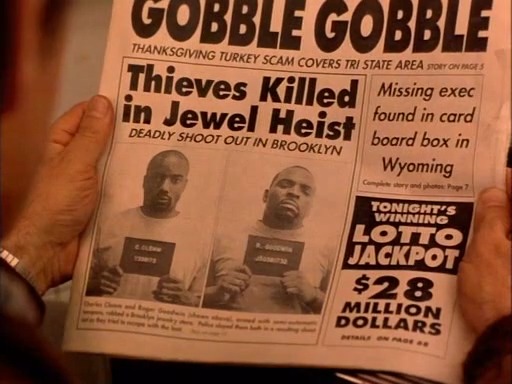

Now, we see a very important insert shot – a close-up of the paper that Auggie is reading, with a front-page story showing that Roger Goodwin and his friend were killed during a jewel heist. This is important for us to know, but it is only revealed to Auggie and us.

Back to the original shot, then we move to an over-the-shoulder shot of Benjamin so that we can see him react, then back to Auggie setting up his story.

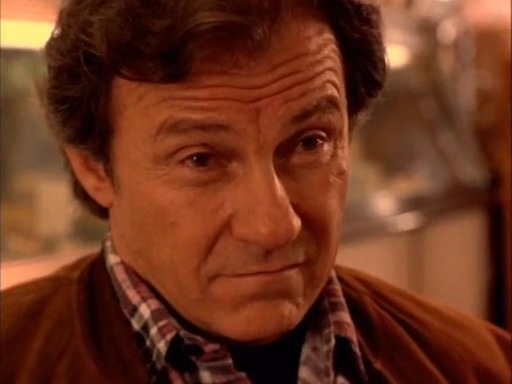

We stick with Benjamin, completely ignoring Auggie, other than the back of his head, until Auggie asks if Benjamin is following him. The story hasn’t started yet, and we’re fixated on the doubtful look on Benjamin’s face.

As Auggie starts to talk about chasing the shoplifter down 7th Avenue, we flip back to Benjamin for his reaction. So far, this is pretty standard shot / reverse shot.

Back to Auggie as he starts to talk about the snapshots he found in the shoplifter’s wallet. We stay with him for more than a minute, this time.

Switch back to Benjamin so we can see how he’s absorbing all of this. We don’t stay on him very long – this scene belongs to Auggie.

Now, we begin the single longest cut of this film.

We have now pushed Benjamin out of the frame. We know that he’s there, silently observing and judging, but we don’t have to see him.

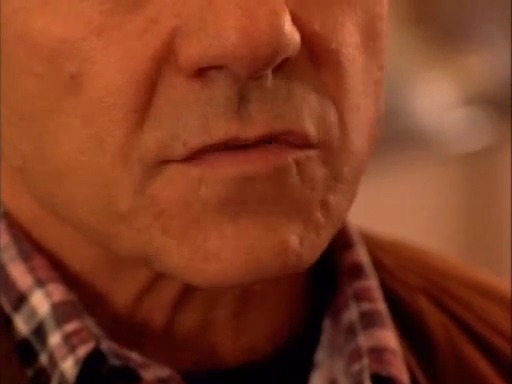

We’re being drawn into Auggie as he tells his story, and logically we’re going to end up staring him in the eyes – right?

Nope. We’re going in for a close-up shot of his mouth. Remember this, it’s about to be very, very relevant.

After all this, we cut back to Benjamin, or rather, a part of him. We’re in as close to him as we are to Auggie, but we’re focusing on his eyes. Benjamin asks Auggie a question, but we don’t waver from his eyes.

Back to Auggie, but wider.

Moving back out, Benjamin a little wider.

Auggie: “Shit, if you can’t share your secrets with your friends, what kind of a friend are you?”

Benjamin: “Exactly. Life just wouldn’t be worth living, would it?”

We know (from earlier) that we were focused on Auggie’s mouth, rather than his eyes – there’s a very heavy inference that his story is mostly fabricated. We saw him read Roger Goodwin’s name off the front of the newspaper, so, much like Verbal Kint’s fabrications in The Usual Suspects (which, incidentally, came out the same year as Smoke), every lie has a kernel of truth in it. It’s also conceivably possible that he’s telling the truth, since his unlikely story could potentially have occurred – Roger Goodwin could have robbed him years ago, he could have had Christmas with his blind grandmother, and he could have stolen the camera. There’s enough ambiguity that we are forced to draw our own conclusions.

This may or may not be subverting a very particular trope of camera motion and movement: drawing in on the narrator of a story, we’re drawn into their point of view and, by extension, their subjective truth.

An additional inference could be made by the scene refusing to show both actors in the same shot. There are no wides to establish where we are ; the widest we see for this scene is the opening shot of Auggie. This works well, however, as the end of the previous scene established the circumstances for this meeting.

There are two possible ways that we could interpret the quote I referenced: either Auggie is telling the truth, is a good friend, and life would be worth living – or – Auggie is fabricating the story, is a bad friend, and life isn’t worth living, which would confirm Benjamin’s dour outlook on life.

One last thing to note is that the script takes a very different approach to this scene. It relies heavily on black-and-white flashbacks to tell the story, with dissolves and stylistic cutting prescribed to force the viewpoint of the story. The actual execution of this scene (which was co-directed by the author of the script, incidentally) uses a far more holistic and natural approach to storytelling. It isn’t “more right” than the script’s approach, but noting its effectiveness is very important in understanding the reasoning involved in choosing to use this approach.

(All images are presented under fair use guidelines – all frame grabs are property of Miramax, or any other entities who hold copyright on this film. They are presented for exclusively educational purposes.)