Daredevil and Falling Down: Character Descent

Comparing similar character development in Marvel's Daredevil and Falling Down

I wouldn’t normally associate the 1993 Schumacher film Falling Down with the Netflix/Marvel Daredevil series, especially since Schumacher didn’t astound me, given the source material he had to work with. However, there is a common thread between the two properties besides their antagonists’ initials – the descent of their characters and how they perceive themselves.

Act I – Establishing a Character: William Foster and Wilson Fisk

Falling Down presents us with a simple premise: a man, William Foster, snaps after a long series of crippling setbacks. Schumacher introduces him with an extreme closeup:

which pulls out to start a very long steadicam shot, revealing his isolation in his car. There is also a very prominent American flag displayed behind his head, revealed to be hung on a nearby bus.

We start with a claustrophobic view of Foster, proceeding to pull outwards and show him as but a single element in a large tapestry of people stuck in the same apparent situation.

The film presents two potential protagonists: Michael Douglas’ William Foster and Robert Duvall’s Prendergast. They both are introduced as neutral characters – although Prendergast is shown, through a number of tried-and-true police tropes, to be a good person, while Foster’s character is taken in a different direction entirely.

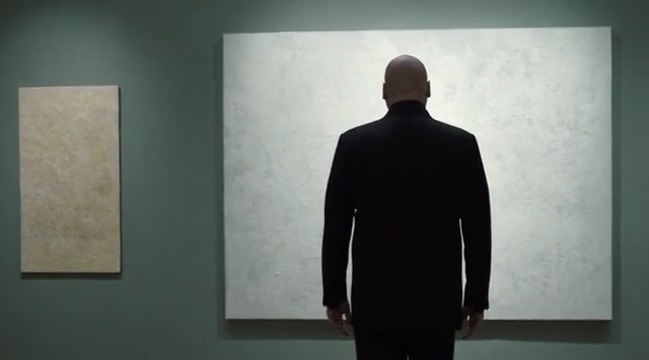

Wilson Fisk is first introduced to us as a mysterious character in the third of thirteen episodes in Daredevil’s first season. Murdock/Daredevil drags his name out of John Healy before he impales himself – and we first see the mysterious Wilson Fisk as the camera pans from left to right across an art gallery.

The art gallery’s owner, Vanessa, approaches him as she attempts to make smalltalk about the painting …

… which she jokes about by comparing to a joke about a “rabbit in a snowstorm”.

Fisk’s face cannot be seen throughout this. He is either left out of the diegetic space or shadowed, much like Frank Costello in The Departed. We are presented an implicit sketch of Fisk’s character in this way – hiding in plain sight, much like the rabbit in the snowstorm.

We first see his whole face as Vanessa asks him how it makes him feel.

Fisk replies that it makes him feel “alone”. The first time we see his face, it is half-shadowed, as if to imply that he is a complex morally ambiguous character.

Act II – Character Development

Foster’s arc is a downward spiral throughout the course of the film. The more information we are given about him and his reactions to the situations with which he is presented, the more we realize that he isn’t a particularly good person. Prendergast is presented as a counterpoint to this character – he is consistently rendered as a good character oppressed by those around him, but he never lashes out as Foster does.

Fisk, like his full-face-half-shadowed introduction, has two parallel character developments. One pertains to the exposition of his criminal enterprises and his interactions with Murdock/Daredevil. This arc is a downward spiral, as Fisk is shown to be a reprehensible character who would kill anyone who stood between him and his vision. The second arc is his character’s internal perception of himself as well as his relationship with Vanessa. He is shown to be a visionary (as seen in his public persona when first revealed) with a bold vision for the future of Hell’s Kitchen, as well as a caring and compassionate man in his relationship with Vanessa.

Act III – Denouement and Realization

Foster is confronted by Prendergast as he tries to meet with his estranged wife and daughter. After Prendergast gets them safely away from Foster, he lays out what he believes to be the most likely scenario which would have unfolded.

Prendergast: “You know exactly what you were gonna do. Kill your wife and child! Then it’d be too late to turn back. It’d be easy to kill yourself. Let’s go meet some nice policemen. They’re good guys. Let’s go.”

Foster: “I’m the bad guy? How did that happen? I did everything they told me to.”

Even though we are aware of his descent from a theoretically ordinary member of society to a violent criminal, he hasn’t been aware of it. We tend to be the most blind when it comes to seeing ourselves, and Foster is no exception. Schumacher presented us with an anti-hero – but he turned out to be the villain. Our tendency would have been to identify with Foster, but we’re left conflicted when we realize that we’ve been sympathizing with the wrong guy. The moral ambiguity of where he became the villain is left up to the reflection of the audience; Foster chooses to kill himself rather than try to fix the shambles of the life he once had.

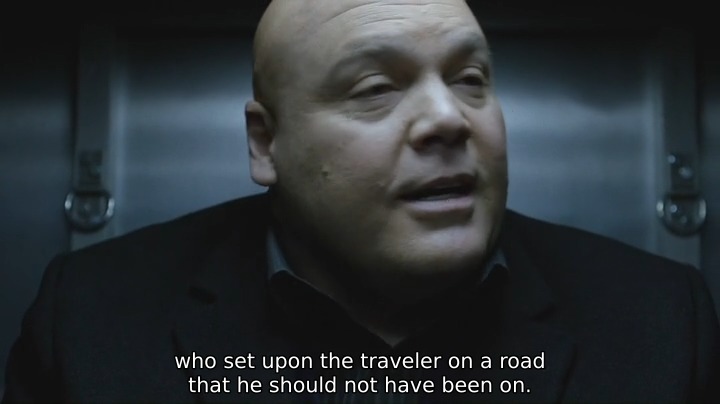

Fisk’s revelation also occurs when he’s confronted with his actions by law enforcement. He is being transported in the back of a police transport, guarded by two heavily armed guards:

Fisk: “I was thinking about a story from the Bible. I’m not a religious man but I’ve read bits and pieces over the years. Curiosity more than faith. But this one story… There was a man. He was traveling from when he was set upon by men of ill intent. They stripped the traveler of his clothes, they beat him, and they left him bleeding in the dirt. And a priest happened by saw the traveler. But he moved to the other side of the road and continued on. And then a Levite, a religious functionary, he came to the place, saw the dying traveler. But he too moved to the other side of the road, passed him by. But then came a man from Samaria, a Samaritan, a good man. He saw the traveler bleeding in the road and he stopped to aid him without thinking of the circumstance or the difficulty it might bring him. The Samaritan tended to the traveler’s wounds, applying oil and wine. And he carried him to an inn, gave him all the money he had for the owner to take care of the traveler, as the Samaritan, he continued on his journey. He did this simply because the traveler was his neighbor. He loved his city and all the people in it. I always thought that I was the Samaritan in that story. It’s funny, isn’t it? How even the best of men can be deceived by their true nature.”

As he tells his story, we draw into Fisk until he’s too large for the frame. The other men in the same physical space as him are only there to bear witness – they will soon be completely irrelevant.

Fisk: “It means that I’m not the Samaritan. That I’m not the priest, or the Levite. That I am the ill intent who set upon the traveler on a road that he should not have been on.”

Although we have, through the narrative of the detective procedural idiom in which we have viewed Murdock and Foggy’s investigation into the corruption in Hell’s Kitchen, have viewed Fisk as the root of the terrible evil we have seen, Fisk has not seen himself that way until now. In a way, Murdock/Daredevil has facilitated the rebirth of Wilson Fisk as Kingpin – a theme that evokes Batman dumping Jack Napier into a vat of chemicals creating the Joker in Tim Burton’s Batman.

Despite violent behavior, including beating people to death with his bare hands (and with an SUV door, in one case), Fisk has seen his actions as being part of a greater good for the city he loves, much as Foster saw his actions as part of a greater good for his family. Neither of these men’s actions were perceived externally as purveying benefits to others, and, until confronted with the harsh truth of others’ perceptions of them, saw themselves as heroes of their own lives. The denouement in both of these works are important because of the perceptual shifts in each of their villains.

It’s interesting to note that, while Foster came to his realization through a direct conflict with the actual protagonist of the film, Prendergast, Fisk was driven to his realization through a culmination of the actions of the actual protagonist of his filmic universe, Murdock/Daredevil. The latter affords, I believe, a more subtle realization and produces a more interesting film experience.

(All images are presented under fair use guidelines – all frame grabs are property of Alcor Films, Canal+, Regency Enterprises, ABC Studios, DeKnight Productions, Goddard Textiles, or any other entities who hold copyright on this film. They are presented for exclusively educational purposes.)