The Monomyth, Saving the Cat, and Consistency

Why do we seem obsessed, as a culture, with films heavily designed around pandering to the Campbellian Monomyth?

Joseph Campbell’s book “The Hero With A Thousand Faces” wasn’t intended to be a blueprint to create stories or films, but it has become that for many auteurs. Why the Monomyth?

The Monomyth

Joseph Campbell outlined a number of common archetypal points, which he believed comprised the common points from a number of mythological sources. He called it the “monomyth” (a reference to James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake). He summarized it as:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

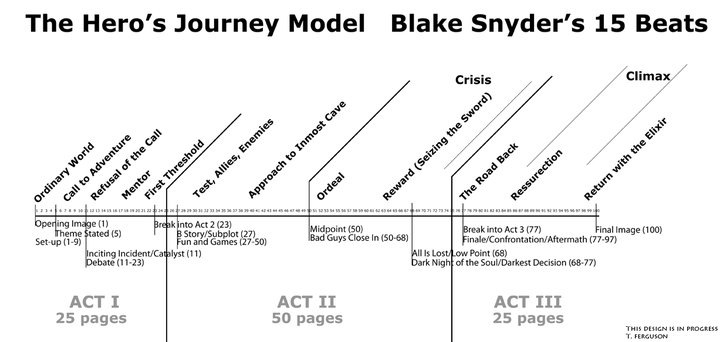

Campbell broke the concept into seventeen stages, which could be divided into the three act structure most commonly found in film and theater: Separation, Initiation, and Return.

The monomyth concept became incredibly pervasive, influencing such properties as Star Wars (where creator George Lucas expressly indicated that he had used Campbell’s work as a reference), Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001, and being subverted by Frank Herbert’s Dune (although eerily partially un-subverted by the Lynch film adaptation thereof).

Blake Snyder’s “Save the Cat” and the age of lazy screenwriting

In the late 1980s, a successful “spec” screenwriter, Blake Snyder, adapted the monomyth concept into a “beat sheet” template for aspiring screenwriters. His title was a reference to the emotional investment an audience takes in a character when they witness that character perform a heroic act – specifically Ripley saving a cat named “Jones” in Alien.

Snyder had publicly stated that he was espousing a structure not a formula, but that hasn’t stopped an outpouring of hate over the formulaic movies it has spawned.

Salty, Sweet, and Fatty

There is a pretty strong theory in the scientific community that our predilection for salty, sweet, and fatty foods is an outgrowth of our evolutionary survival needs, since food availability pre-agricultural-revolution was not necessarily guaranteed in most populations. This seems like an utterly harmless observation, until it is coupled with shareholder expectations for unbounded profits in the food industry. We end up with a push to create food-like substances which push certain evolutionary triggers in our physiology, causing us to be drawn towards them – eventually creating an arms race to create the most attractive food-like substance to create the highest level of profit for the company producing those substances.

Pushing buttons and the race to the bottom

The Campbellian Monomyth, as well as instructive derivatives like Save the Cat, offer a satisfying story which pushes all of the right buttons so that we will eventually make the “correct” consumer choices – watching their films, reading their books, and ultimately holding up their bottom line.

The story about bad behavior in systems to which I tend to refer is The Parable of the Tribes, in which the behavior of those in a system is dictated by the worst in that system. It describes the “race to the bottom” in US State-level regulations for businesses, and also describes the behavior of self-interested entities producing films. If you know that pushing an evolutionarily-defined button is going to produce additional profit, you’re not going to let your competitor have that advantage. The same effect can be seen in the teal and orange color grading epidemic in the last decade or so.

This is not intended as a dismissal or attack of Campbell’s work, or any of his contemporaries – this is very specifically an issue that quite a few people have with the intellectual laziness stemming from using Campbell’s work as a shortcut.

Everything has its place

At first glance, it’s easy to read all of this as building towards a dismissal of any piece centering around the monomyth; nothing could be further from the truth.

I have been wrestling with the concept that things have their place, and that even if I personally don’t particularly care for them, other people might find some use or satisfaction related to them.

The monomyth and its formulaic corollaries aren’t specifically instructions for creating pablum, but rather a description for archetypal stories which predate our current civilizations – what could be considered a safe, tried-and-true description of how to properly tell a compelling story which will enrapture the majority of its audience.

Not every theater-going experience has to be a series of mental calisthenics, although I will admit that delving into film analysis and theory has ruined some of the surprise and awe for me – much in the same way that any sense of wonder or amazement can be dulled by a comprehensive understanding of the less-than-supernatural nature of things. (This is actually one of the reasons why I prefer that stories not engage in annoyingly comprehensive epistemological completion in their respective knowledge systems, since my imagination tends to be more interesting than most rote knowledge completions – but I digress.)

Sometimes, you have to be able to go somewhere and turn off your brain for a bit and enjoy something that feels good, even if it is derivative, or overplayed, or just plain guilty indulgence. In this aspect, the film properties heavily derived from Save the Cat (or even the monomyth directly) can be seen as having their place.